Overview

This Guidelines summary covers the longer-term (rehabilitation) management of acute coronary syndromes. These include ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina. The guideline does not cover management of spontaneous coronary artery dissection.

This summary only includes recommendations applicable to primary care settings. For the full set of recommendations, refer to the full guideline.

Reflecting on Your Learnings

Reflection is important for continuous learning and development, and a critical part of the revalidation process for UK healthcare professionals. Click here to access the Guidelines Reflection Record.

Hyperglycaemia in Acute Coronary Syndromes

Advice and Ongoing Monitoring for People with Hyperglycaemia after Acute Coronary Syndrome and Without Known Diabetes

- Offer people with hyperglycaemia after acute coronary syndrome and without known diabetes lifestyle advice on the following:

- healthy eating

- physical exercise

- weight management

- smoking cessation

- alcohol consumption

- Advise people without known diabetes that if they have had hyperglycaemia after an acute coronary syndrome, they:

- are at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes

- should consult their GP if they experience the following symptoms:

- frequent urination

- excessive thirst

- weight loss

- fatigue

- should be offered tests for diabetes at least annually

- Offer at least annual monitoring of HbA1c and fasting blood glucose levels to people without known diabetes who have had hyperglycaemia after an acute coronary syndrome.

Drug Therapy for Secondary Prevention

- For secondary prevention, offer people who have had MI treatment with the following drugs:

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor

- dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin plus a second antiplatelet) unless they have a separate indication for anticoagulation (see the section on antiplatelet therapy for people with an ongoing separate indication for anticoagulation)

- beta-blocker

- statin

- Ensure that a clear management plan is available to the person who has had an MI and is also sent to the GP, including:

- details and timing of any further drug titration

- monitoring of blood pressure

- monitoring of renal function

- Offer all people who have had an MI an assessment of bleeding risk at their follow-up appointment.

- NICE guideline on medicines adherence

- NICE guideline on cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and risk reduction, including lipid modification

- NICE technology appraisal guidance on alirocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia

- NICE technology appraisal guidance on evolocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia

- NICE technology appraisal guidance on rivaroxaban for preventing atherothrombotic events in people with coronary or peripheral artery disease.

ACE Inhibitors

- Offer people who present acutely with an MI, an ACE inhibitor as soon as they are haemodynamically stable. Continue the ACE inhibitor indefinitely

- Titrate the ACE inhibitor dose upwards at short intervals (for example, every 12 to 24 hours) before the person leaves hospital until the maximum tolerated or target dose is reached. If it is not possible to complete the titration during this time, it should be completed within 4 to 6 weeks of hospital discharge

- Do not offer combined treatment with an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) to people after an MI, unless there are other reasons to use this combination

- After an MI, offer people who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors, an ARB instead of an ACE inhibitor

- Renal function, serum electrolytes and blood pressure should be measured before starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB and again within 1 or 2 weeks of starting treatment. People should have appropriate monitoring as the dose is titrated upwards, until the maximum tolerated or target dose is reached, and then at least annually. More frequent monitoring may be needed in people who are at increased risk of deterioration in renal function. People with chronic heart failure should be monitored in line with the NICE guideline on chronic heart failure in adults

- Offer an ACE inhibitor to people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago. Titrate to the maximum tolerated or target dose (over a 4- to 6-week period) and continue indefinitely

- Offer people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago and who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors an ARB instead of an ACE inhibitor.

Antiplatelet Therapy

- Offer aspirin to all people after an MI and continue it indefinitely, unless they are aspirin intolerant or have an indication for anticoagulation (see the section on antiplatelet therapy for people with an ongoing separate indication for anticoagulation)

- Offer aspirin to people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago and continue it indefinitely

- Continue dual antiplatelet therapy for up to 12 months after an MI unless contraindicated

- For people with aspirin hypersensitivity who have had an MI, clopidogrel monotherapy should be considered as an alternative treatment

- People with a history of dyspepsia should be considered for treatment in line with the NICE guideline on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults

- After appropriate treatment, people with a history of aspirin-induced ulcer bleeding whose ulcers have healed and who are negative for Helicobacter pylori should be considered for treatment in line with the NICE guideline on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults

- Offer clopidogrel instead of aspirin to people who also have other clinical vascular disease, in line with the NICE technology appraisal guidance on clopidogrel and modified-release dipyridamole for the prevention of occlusive vascular events, and who have:

- had an MI and stopped dual antiplatelet therapy or

- had an MI more than 12 months ago.

Antiplatelet Therapy for People with an Ongoing Separate Indication for Anticoagulation

- For people who have a separate indication for anticoagulation, take into account all of the following when thinking about the duration and type (dual or single) of antiplatelet therapy in the 12 months after an acute coronary syndrome:

- bleeding risk

- thromboembolic risk

- cardiovascular risk

- person’s wishes

- Be aware that the optimal duration of aspirin therapy has not been established, and that long-term continuation of aspirin, clopidogrel and oral anticoagulation (triple therapy) significantly increases bleeding risk

- For people already on anticoagulation who have had percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI),continue anticoagulation and clopidogrel for up to 12 months. If the person is taking a direct oral anticoagulant, adjust the dose according to bleeding risk, thromboembolic risk and cardiovascular risk

- For people with a new indication for anticoagulation who have had PCI, offer clopidogrel (to replace prasugrel or ticagrelor) for up to 12 months and an oral anticoagulant licensed for the indication, which best matches the person’s:

- bleeding risk

- thromboembolic risk

- cardiovascular risk

- wishes

- For people already on anticoagulation, or those with a new indication, who have not had PCI (medical management, CABG), continue anticoagulation and, unless there is a high risk of bleeding, consider continuing aspirin (or clopidogrel for people with contraindication for aspirin) for up to 12 months

- Do not routinely offer prasugrel or ticagrelor in combination with an anticoagulant that is needed for an ongoing separate indication for anticoagulation

- For people with an ongoing indication for anticoagulation 12 months after an MI, take into consideration all of the following when thinking about the need for continuing antiplatelet therapy:

- indication for anticoagulation

- bleeding risk

- thromboembolic risk

- cardiovascular risk

- person’s wishes.

Beta-blockers

- Offer people a beta-blocker as soon as possible after an MI, when the person is haemodynamically stable

- Communicate plans for titrating beta-blockers up to the maximum tolerated or target dose—for example, in the discharge summary

- Consider continuing a beta-blocker for 12 months after an MI for people without reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Discuss the potential benefits and risks of stopping or continuing beta-blockers beyond 12 months after an MI for people without reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Include in the discussion:

- the lack of evidence on the relative benefits and harms of continuing beyond 12 months

- the person’s experience of adverse effects

- Continue a beta-blocker indefinitely in people with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Offer all people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago, who have reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, a beta-blocker whether or not they have symptoms. For people with heart failure plus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, manage the condition in line with the NICE guideline on chronic heart failure in adults

- Do not offer people without reduced left ventricular ejection fraction or heart failure, who have had an MI more than 12 months ago, treatment with a beta-blocker unless there is an additional clinical indication for a beta-blocker.

Calcium Channel Blockers

- Do not routinely offer calcium channel blockers to reduce cardiovascular risk after an MI

- If beta-blockers are contraindicated or need to be discontinued, diltiazem or verapamil may be considered for secondary prevention in people without pulmonary congestion or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- For people whose condition is stable after an MI, calcium channel blockers may be used to treat hypertension and/or angina. For people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, use amlodipine, and avoid verapamil, diltiazem and short-acting dihydropyridine agents in line with the NICE guideline on chronic heart failure in adults

Potassium Channel Activators

- Do not offer nicorandil to reduce cardiovascular risk after an MI.

Aldosterone Antagonists in People with Heart Failure and Reduced Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

- For people who have had an acute MI and who have symptoms and/or signs of heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, initiate treatment with an aldosterone antagonist licensed for post-MI treatment within 3 to 14 days of the MI, preferably after ACE inhibitor therapy

- People who have recently had an acute MI and have clinical heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, but who are already being treated with an aldosterone antagonist for a concomitant condition (for example, chronic heart failure), should continue with the aldosterone antagonist or an alternative, licensed for early post-MI treatment

- For people who have had a proven MI in the past and heart failure due to reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, treatment with an aldosterone antagonist should be in line with the NICE guideline on chronic heart failure in adults

- Monitor renal function and serum potassium before and during treatment with an aldosterone antagonist. If hyperkalaemia is a problem, halve the dose of the aldosterone antagonist or stop the drug.

Cardiac Rehabilitation after an MI

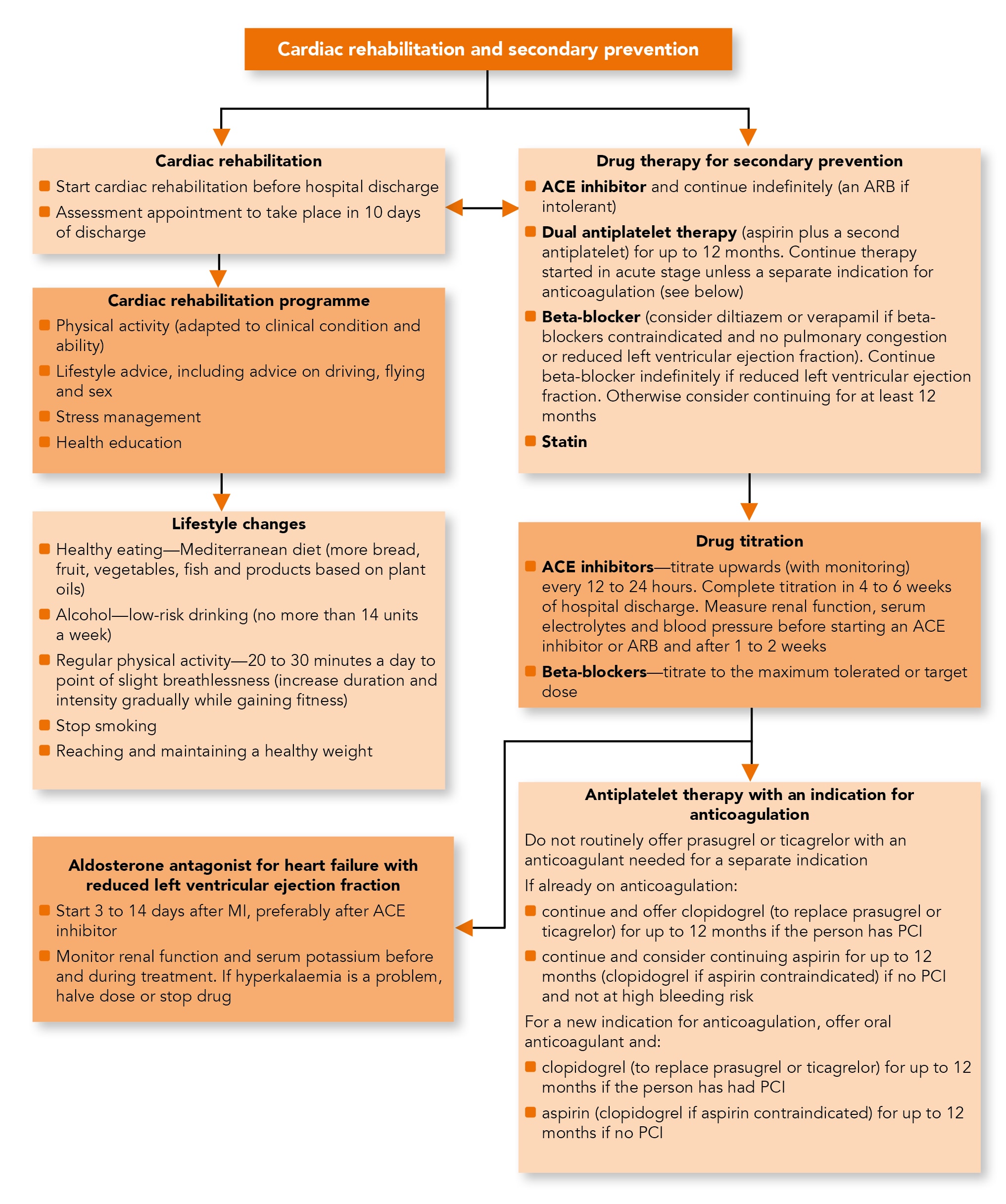

Algorithm 1: Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention

- All people (regardless of their age) should be given advice about and offered a cardiac rehabilitation programme with an exercise component

- Cardiac rehabilitation programmes should provide a range of options, and people should be encouraged to attend all those appropriate to their clinical needs. People should not be excluded from the entire programme if they choose not to attend certain components

- If a person has cardiac or other clinical conditions that may worsen during exercise, these should be treated if possible before they are offered the exercise component of cardiac rehabilitation. For some people, the exercise component may be adapted by an appropriately qualified healthcare professional

- People with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction who are stable can safely be offered the exercise component of cardiac rehabilitation.

Encouraging People to Attend

- Deliver cardiac rehabilitation in a non-judgemental, respectful and culturally sensitive manner. Consider employing bilingual peer educators or cardiac rehabilitation assistants who reflect the diversity of the local population

- Establish people’s health beliefs and their specific illness perceptions before offering appropriate lifestyle advice and to encourage attendance to a cardiac rehabilitation programme

- Offer cardiac rehabilitation programmes designed to motivate people to attend and complete the programme. Explain the benefits of attending

- Discuss with the person any factors that might stop them attending a cardiac rehabilitation programme, such as transport difficulties

- Offer cardiac rehabilitation programmes in a choice of venues (including at the person’s home, in hospital and in the community) and at a choice of times of day, for example, sessions outside of working hours. Explain the options available

- Provide a range of different types of exercise, as part of the cardiac rehabilitation programme, to meet the needs of people of all ages, or those with significant comorbidity. Do not exclude people from the whole programme if they choose not to attend specific components

- Offer single-sex cardiac rehabilitation programme classes if there is sufficient demand

- Enrol people who have had an MI in a system of structured care, ensuring that there are clear lines of responsibility for arranging the early initiation of cardiac rehabilitation

- Begin cardiac rehabilitation as soon as possible after admission before discharge from hospital, and invite the person to a cardiac rehabilitation session. This should start within 10 days of their discharge from hospital

- Contact people who do not start or do not continue to attend the cardiac rehabilitation programme with a further reminder, such as:

- a motivational letter

- a prearranged visit from a member of the cardiac rehabilitation team

- a telephone call

- a combination of the above

- Seek feedback from cardiac rehabilitation programme users and aim to use this feedback to increase the number of people starting and attending the programme

- Be aware of the wider health and social care needs of a person who has had an MI. Offer information and sources of help on:

- economic issues

- welfare rights

- housing and social support issues

- Make cardiac rehabilitation equally accessible and relevant to all people after an MI, particularly people from groups that are less likely to access this service. These include people from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, older people, people from lower socioeconomic groups, women, people from rural communities, people with a learning disability and people with mental and physical health conditions

- Encourage all staff, including senior medical staff, involved in providing care for people after an MI, to actively promote cardiac rehabilitation.

Health Education and Information Needs

- Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programmes should include health education and stress management components

- A home-based programme validated for people who have had an MI that incorporates education, exercise and stress management components with follow ups by a trained facilitator may be used to provide comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation

- Take into account the physical and psychological status of the patient, the nature of their work and their work environment when giving advice on returning to work

- Be up to date with the latest Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) guidelines. Regular updates are published by the DVLA

- After an MI without complications, people who wish to travel by air should seek advice from the Civil Aviation Authority. People who have had a complicated MI need expert individual advice

- People who have had an MI who hold a pilot’s licence should seek advice from the Civil Aviation Authority

- Take into account the person’s physical and psychological status, as well as the type of activity planned when offering advice about the timing of returning to normal activities

- An estimate of the physical demand of a particular activity, and a comparison between activities, can be made using tables of metabolic equivalents (METS) of different activities. Advise people how to use a perceived exertion scale to help monitor physiological demand. People who have had a complicated MI may need expert advice

- Advice on competitive sport may need expert assessment of function and risk, and is dependent on what sport is being discussed and the level of competitiveness.

Psychological and Social Support

- Offer stress management in the context of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation

- Do not routinely offer complex psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy

- Involve partners or carers in the cardiac rehabilitation programme if the person wishes. For recommendations on managing clinical anxiety or depression, refer to the NICE guidelines on anxiety, depression in adults and depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem.

Sexual Activity

- Reassure people that after recovery from an MI, sexual activity presents no greater risk of triggering a subsequent MI than if they had never had an MI

- Advise people who have made an uncomplicated recovery after their MI that they can resume sexual activity when they feel comfortable to do so, usually after about 4 weeks

- Raise the subject of sexual activity within the context of cardiac rehabilitation and aftercare for people who have had an MI.

Lifestyle Changes after an MI

Changing Diet, Alcohol Consumption and Regular Physical Activity

- Advise people to eat a Mediterranean-style diet (more bread, fruit, vegetables and fish; less meat; and replace butter and cheese with products based on plant oils)

- Do not routinely recommend eating oily fish for the sole purpose of preventing another MI. If people choose to consume oily fish after an MI, be aware that there is no evidence of harm, and fish may form part of a Mediterranean-style diet

- Do not offer or advise people to use the following to prevent another MI:

- omega-3 fatty acid capsules

- omega-3 fatty acid supplemented foods

- If people choose to take omega-3 fatty acid capsules or eat omega-3 fatty acid supplemented foods, be aware that there is no evidence of harm

- Advise people not to take supplements containing beta-carotene. Do not recommend antioxidant supplements (vitamin E and/or C) or folic acid to reduce cardiovascular risk

- Offer people an individual consultation to discuss diet, including their current eating habits, and advice on improving their diet

- Give people consistent dietary advice tailored to their needs

- Give people healthy eating advice that can be extended to the whole family

- For advice on alcohol consumption, see the UK government drinking guidelines

- Advise people to undertake regular physical activity sufficient to increase exercise capacity. Advise people to be physically active for 20 to 30 minutes a day to the point of slight breathlessness. Advise people who are not active to this level to increase their activity in a gradual, step-by-step way, aiming to increase their exercise capacity. They should start at a level that is comfortable, and increase the duration and intensity of activity as they gain fitness

- Advice on physical activity should involve a discussion about current and past activity levels and preferences. The benefit of exercise may be enhanced by tailored advice from a suitably qualified professional

Smoking Cessation

- Advise all people who smoke to stop and offer assistance from a smoking cessation service in line with the NICE guideline on stop smoking interventions and services

- If a person is unable or unwilling to accept a referral to a stop smoking service, they should be offered pharmacotherapy in line with the NICE guideline on stop smoking interventions and services.

Weight Management

- After an MI, offer all people who are overweight or obese advice and support to achieve and maintain a healthy weight in line with the NICE guideline on obesity.