Overview

This Guidelines summary is part of a series of summaries of the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guideline 158: British guideline on the diagnosis and management of asthma.

This summary focuses on recommendations for the management of asthma in children, including diagnosis, monitoring, pharmacological management, and management of acute asthma in children in general practice. For the complete set of recommendations, please refer to the full guideline.

Follow the links for summaries of BTS/SIGN recommendations on the diagnosis and management of asthma in the following groups:

Grades of Recommendation

The grade of recommendation relates to the strength of the supporting evidence on which the evidence is based. It does not reflect the clinical importance of the recommendation.[A] At least one meta-analysis, systematic review, or RCT rated as 1++, and directly applicable to the target population; or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+, directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results.

[B] A body of evidence including studies rated as 2++, directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 1++ or 1.

[C] A body of evidence including studies rated as 2+, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2++.

[D] Evidence level 3 or 4; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+.

Good-practice Points

[✓] Recommended best practice based on the clinical experience of the guideline development group.

For the full key of evidence statements and recommendations, please see the full guideline.

Diagnosis

- [C] Compare the results of diagnostic tests undertaken whilst a patient is asymptomatic with those undertaken when a patient is symptomatic to detect variation over time.

Initial Structured Clinical Assessment

The predictive value of individual symptoms or signs is poor, and a structured clinical assessment including all information available from the history, examination and historical records should be undertaken. Factors to consider in an initial structured clinical assessment include:

Episodic Symptoms

- More than one of the symptoms of wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness and cough occurring in episodes with periods of no (or minimal) symptoms between episodes. Note that this excludes cough as an isolated symptom in children. For example:

- a documented history of acute attacks of wheeze, triggered by viral infection or allergen exposure with symptomatic and objective improvement with time and/or treatment

- recurrent intermittent episodes of symptoms triggered by allergen exposure as well as viral infections and exacerbated by exercise and cold air, and emotion or laughter in children

- An historical record of significantly lower FEV₁ or PEF during symptomatic episodes compared with asymptomatic periods provides objective confirmation of the obstructive nature of the episodic symptoms.

Wheeze Confirmed by a Healthcare Professional on Auscultation

- It is important to distinguish wheezing from other respiratory noises, such as stridor or rattly breathing

- Repeatedly normal examination of chest when symptomatic reduces the probability of asthma.

Evidence of Diurnal Variability

- Symptoms which are worse at night or in the early morning.

Atopic History

- Personal history of an atopic disorder (ie eczema or allergic rhinitis) or a family history of asthma and/or atopic disorders, potentially corroborated by a previous record of raised allergen-specific IgE levels, positive skin-prick tests to aeroallergens or blood eosinophilia.

Assess Probability of Asthma Based on Initial Structured Clinical Assessment

| Please refer to the full guideline for recommendations on high, intermediate, and low probability of asthma. See below for diagnostic algorithm. |

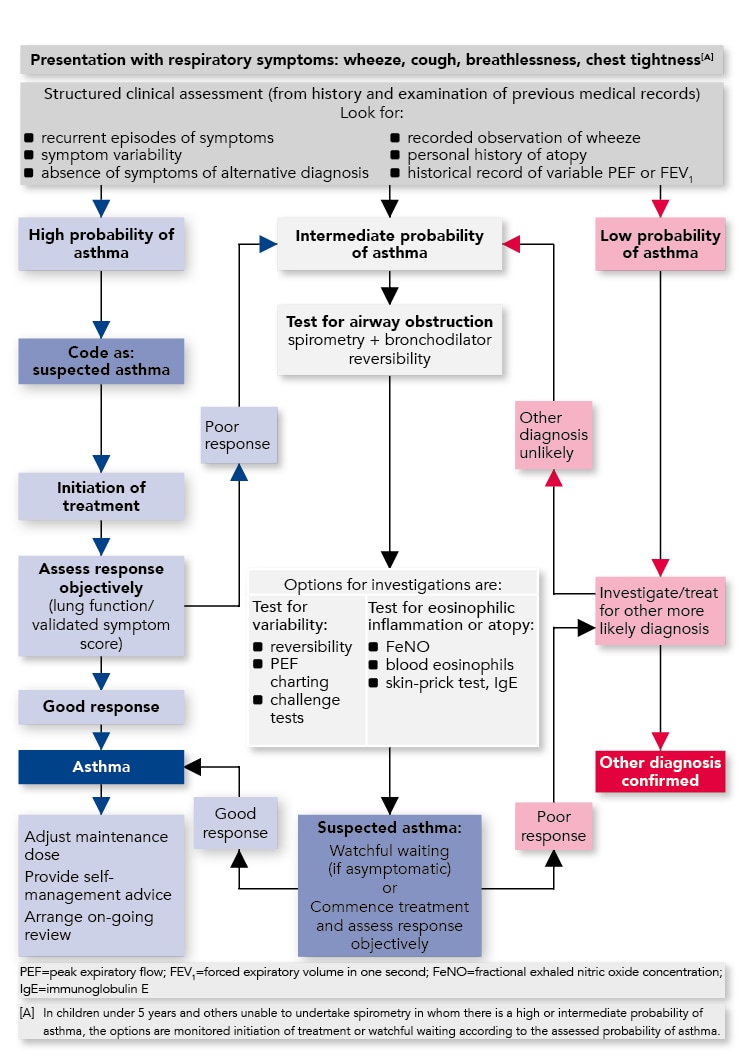

Algorithm for the Diagnosis of Asthma in Children

Diagnostic Indications for Referral

At any point in the diagnostic algorithm, there may be a need for referral for additional investigations and/or specialist advice. Some key indications for referral to specialist care are given below.Refer children for additional investigation and specialist advice if:

|

Monitoring

- [✓] The core components of an asthma review that should be assessed and recorded on at least an annual basis are current symptoms, future risk of attacks, management strategies, supported self management, and growth in children.

Monitoring Current Asthma Symptom Control

- [✓] When asking about asthma symptoms, use specific questions, such as the Royal College of Physicians ‘3 Questions’ or questions about reliever use, with positive responses prompting further assessment with a validated questionnaire to assess symptom control

- [✓] Whenever practicable, children should be asked about their own symptoms; do not rely solely on parental report.

Supported Self-management

Please refer to the full guideline for recommendations on supported self-management (including personalised asthma action plans [PAAPs]).

Non-pharmacological Management

Please refer to the full guideline for recommendations on non-pharmacological management (including primary and secondary prevention).

Pharmacological Management

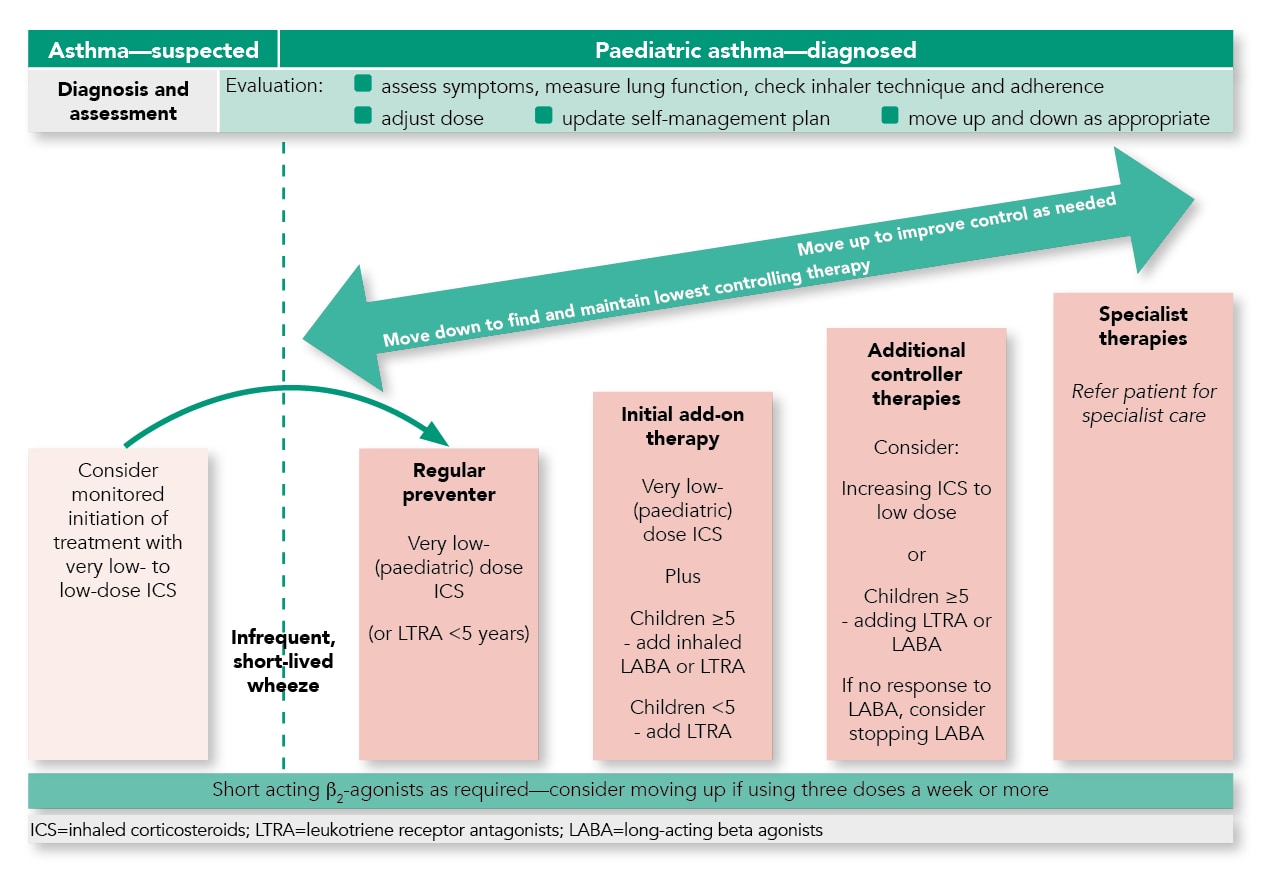

Summary of the Pharmacological Management of Asthma in Children

- The aim of asthma management is control of the disease. Complete control is defined as:

- no daytime symptoms

- no night-time awakening due to asthma

- no need for rescue medication

- no asthma attacks

- no limitations on activity including exercise

- normal lung function (in practical terms FEV₁ and/or PEF >80% predicted or best)

- minimal side effects from medication

- See above for summary of pharmacological management in children.

Approach to Management

- Start treatment at the level most appropriate to initial severity

- Achieve early control

- Maintain control by:

- increasing treatment as necessary

- decreasing treatment when control is good.

- [✓] Before initiating a new drug therapy practitioners should check adherence with existing therapies, check inhaler technique and eliminate trigger factors.

Intermittent Reliever Therapy

- Prescribe an inhaled short-acting β₂ agonist as short-term reliever therapy for all patients with symptomatic asthma [B] 5–12 years; [D] <5 years.

Regular Preventer Therapy

- Inhaled corticosteroids are the recommended preventer drug for children for achieving overall treatment goals [A] 5–12 years; [A] <5 years

- Give inhaled corticosteroids initially twice daily (except ciclesonide which is given once daily) [A] 5–12 years; [A] <5 years

- Once-a-day inhaled corticosteroids at the same total daily dose can be considered if good control is established [A] 5–12 years

- Summary tables categorising inhaled corticosteroids by dose in children for different types of inhaler are included in the full guideline (Table 13) and are available to download separately from the asthma guideline web page at www.sign.ac.uk.

Initial Add-on Therapy

- Before initiating a new drug therapy practitioners should recheck adherence and inhaler technique and eliminate trigger factors

- In children aged five and over, an inhaled long-acting β₂ agonist or a leukotriene receptor antagonist can be considered as initial add-on therapy [B] 5–12 years.

Combination Inhalers

- In efficacy studies, where there is generally good adherence, there is no difference in efficacy in giving inhaled corticosteriod and a long-acting β₂ agonist in combination or in separate inhalers. In clinical practice, however, it is generally considered that combination inhalers aid adherence and also have the advantage of guaranteeing that the long-acting β₂ agonist is not taken without the inhaled corticosteroid

- Combination inhalers are recommended to:

- [✓] guarantee that the long-acting β₂ agonist is not taken without inhaled corticosteroid

- [✓] improve inhaler adherence.

Additional Controller Therapies

- If control remains poor on very low-dose (children aged five and over) inhaled corticosteroids plus a long-acting β₂ agonist, recheck the diagnosis, assess adherence to existing medication and check inhaler technique before increasing therapy

- If asthma control remains suboptimal after the addition of an inhaled long-acting β₂ agonist then [D] 5–12 years:

- increase the dose of inhaled corticosteroids from very low dose to low dose in children (5–12 years), if not already on this dose

or

- consider adding a leukotriene receptor antagonist.

- increase the dose of inhaled corticosteroids from very low dose to low dose in children (5–12 years), if not already on this dose

Specialist Therapies

- [✓] All patients whose asthma is not adequately controlled on recommended initial or additional controller therapies should be referred for specialist care.

Decreasing Treatment

- [✓] Regular review of patients as treatment is decreased is important. When deciding which drug to decrease first and at what rate, the severity of asthma, the side effects of the treatment, time on current dose, the beneficial effect achieved, and the patient’s preference should all be taken into account

- [✓] Patients should be maintained at the lowest possible dose of inhaled corticosteroid. Reduction in inhaled corticosteroid dose should be slow as patients deteriorate at different rates. Reductions should be considered every three months, decreasing the dose by approximately 25–50% each time.

Exercise-induced Asthma

- [✓] For most patients, exercise-induced asthma is an expression of poorly-controlled asthma and regular treatment including inhaled corticosteroids should be reviewed

- If exercise is a specific problem in patients taking inhaled corticosteroids who are otherwise well controlled, consider adding one of the following therapies:

- leukotriene receptor antagonists [C] 5–12 years

- long-acting β₂ agonists [A] 5–12 years

- sodium cromoglicate or nedocromil sodium [C] 5–12 years

- theophyllines [C] 5–12 years

- Immediately prior to exercise, inhaled short-acting β₂ agonists are the drug of choice [A] 5–12 years.

Inhaler Devices

Technique and Training

- Prescribe inhalers only after patients have received training in the use of the device and have demonstrated satisfactory technique [✓] 5–12 years; [✓] <5 years.

β₂ agonist Delivery

Acute Asthma

- Children with mild and moderate asthma attacks should be treated with a pMDI + spacer with doses titrated according to clinical response [A] 5–12 years; [B] <5 years.

Stable Asthma

- In children aged 5–12, a pMDI + spacer is as effective as any other hand-held inhaler [A] 5–12 years.

Inhaled Corticosteroids for Stable Asthma

- In children aged 5–12, a pMDI + spacer is as effective as any other hand-held inhaler [A] 5–12 years.

Prescribing Devices

- [✓] The choice of device may be determined by the choice of drug

- [✓] If the patient is unable to use a device satisfactorily an alternative should be found

- [✓] The patient should have their ability to use the prescribed inhaler device (particularly for any change in device) assessed by a competent healthcare professional

- [✓] The medication needs to be titrated against clinical response to ensure optimum efficacy

- [✓] Reassess inhaler technique as part of the structured clinical review

- [✓] Generic prescribing of inhalers should be avoided as this might lead to people with asthma being given an unfamiliar inhaler device which they are not able to use properly

- [✓] Prescribing mixed inhaler types may cause confusion and lead to increased errors in use. Using the same type of device to deliver preventer and reliever treatments may improve outcomes.

Inhaler Devices in Children

- In young children, little or no evidence is available on which to base recommendations

- In children, a pMDI and spacer is the preferred method of delivery of β₂ agonists and inhaled corticosteroids. A face mask is required until the child can breathe reproducibly using the spacer mouthpiece. Where this is ineffective a nebuliser may be required [✓] ≥1 years.

Management of Acute Asthma in Children in General Practice

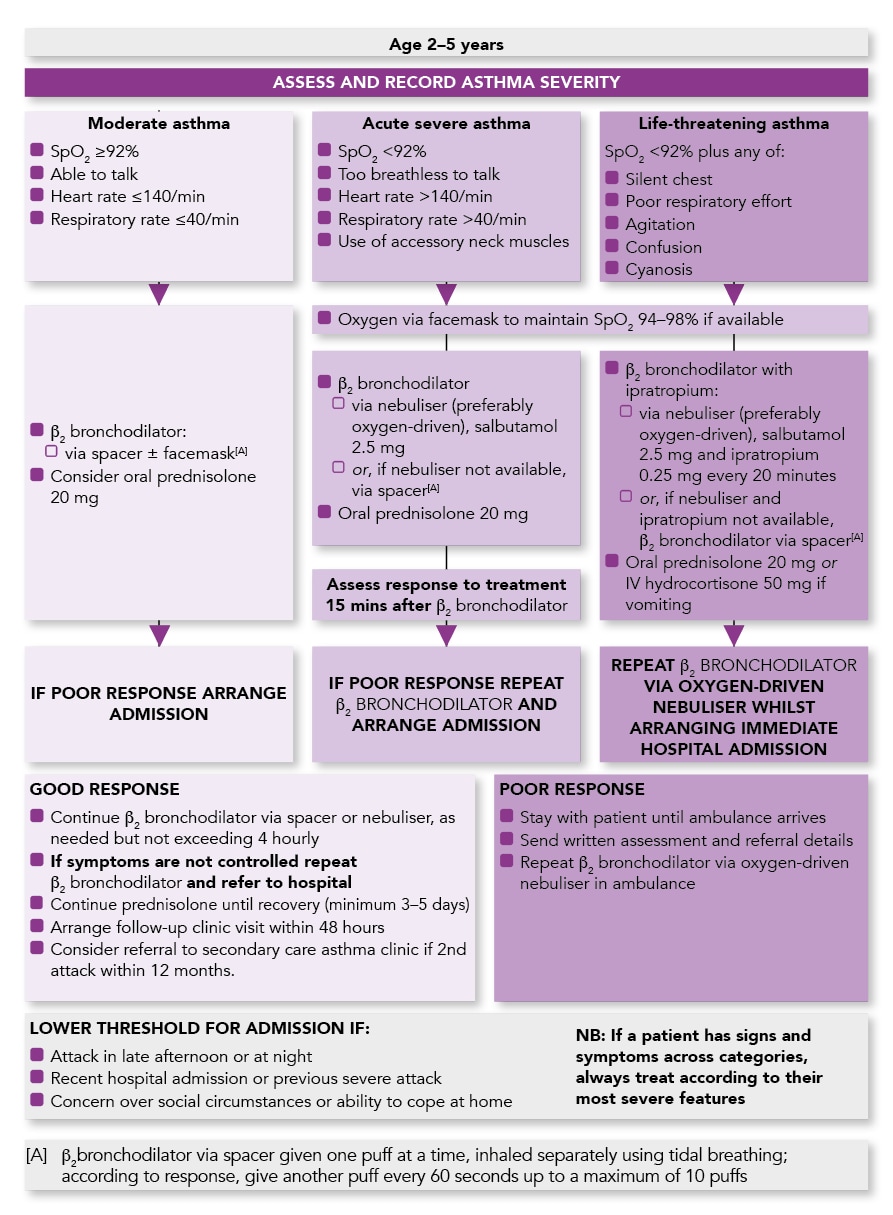

Algorithm of the Management of Acute Asthma in Children aged 2–5 Years in General Practice

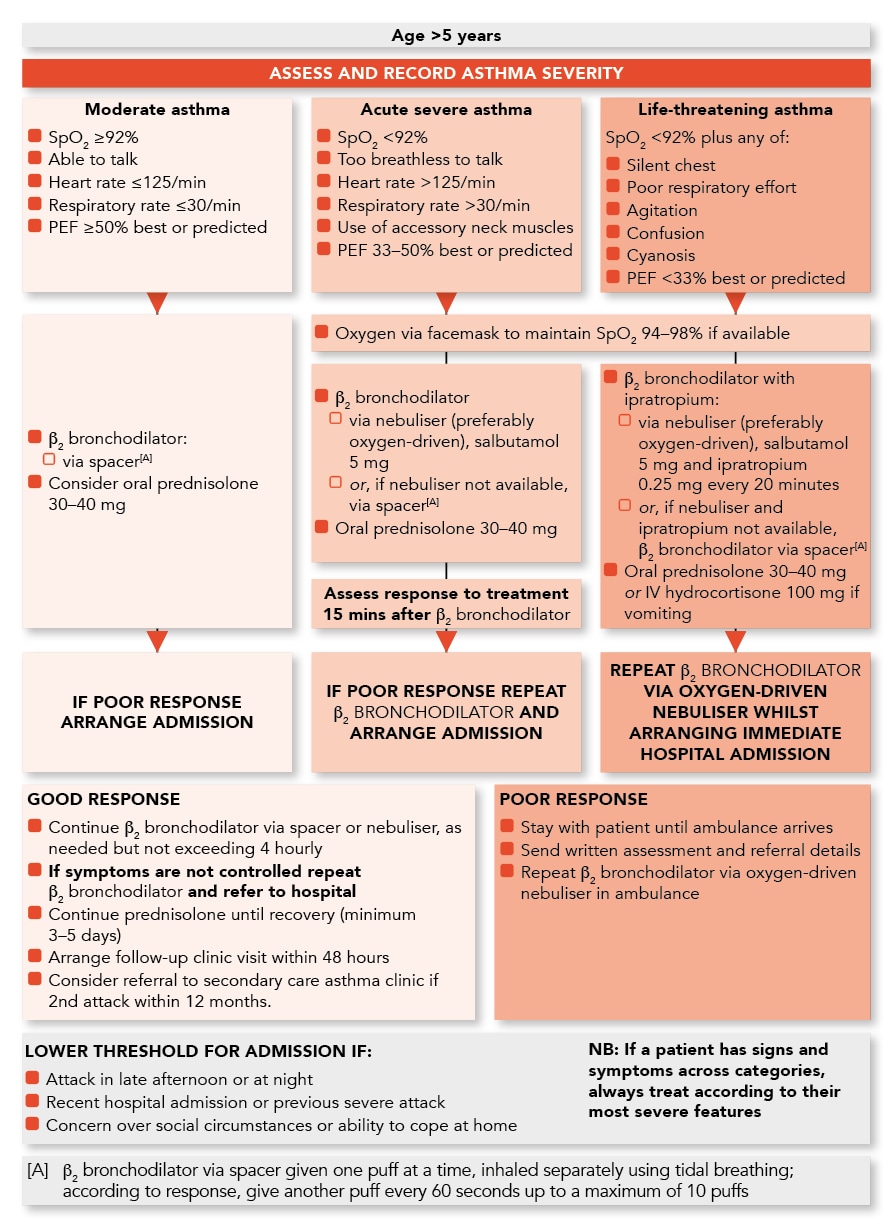

Algorithm of the Management of Acute Asthma in Children aged Over 5 Years in General Practice