Overview

This Guidelines summary covers key recommendations for GPs on interpreting results from liver blood tests and responding to detected abnormalities. It includes a useful algorithm on clinical pattern recognition for liver blood tests. For a complete set of recommendations, refer to the full guideline.

Investigations

- Initial investigation for potential liver disease should include bilirubin, albumin, alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT), together with a full blood count if not already performed within the previous 12 months.

When Should Liver Blood Tests be Checked?

- Non-specific symptoms (for example, fatigue, nausea, or anorexia in autoimmune hepatitis)

- Evidence of chronic liver disease (for example, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, liver failure)

- Conditions which are associated with a high risk of developing liver disease, such as:

- pre-existing autoimmune disease

- patients with inflammatory bowel disease (including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease)

- Use of hepatotoxic drugs (for example, carbamezepine, methyldopa, minocycline, macrolide antibiotics)

- Family history of liver diseases (for example, haemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease)

- Viral hepatitis

- while liver blood tests can give an indication of necro-inflammation or of advanced fibrosis, a key early test is serology for viral hepatitis in high-risk groups as liver blood tests can be normal in this setting (Table 1)

- Presence of lifestyle risk factors associated with the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (for example, obesity, type 2 diabetes).

Table 1: Liver Aetiology Table for Patients with Non-acute Abnormal Liver Blood Tests

| Standard Liver Aetiology Panel | Extended Liver Aetiology Panel | |

|---|---|---|

| Viral hepatitis | Hepatitis B surface antigen AND hepatitis C antibody (with follow-on PCR if positive) | Anti-HBc and anti-HBs hepatitis B DNA quantification of hepatitis delta in high-prevalence areas |

| Iron overload | Ferritin AND transferrin saturation | Haemochromatosis gene testing |

| Autoimmune liver disease (excluding PSC) | Anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, antinuclear antibody, serum immunoglobulins | Anti-LKM antibody and coeliac antibodies (consider ANCA in the presence of cholestatic liver blood tests) |

| Metabolic liver disease | Alpha-1-antitrypsin level; thyroid function tests; caeruloplasmin (age >3 and <40 years) ± urinary copper collection | |

| PCR=polymerase chain reaction; PSC=primary sclerosing cholangitis; LKM=liver kidney miscrosome; ANCA=antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. | ||

Does the Extent and Duration of Abnormal Liver Blood Tests Determine Subsequent Investigation?

- Abnormal liver blood test results should only be interpreted after review of the previous results, past medical history and current medical condition

- The extent of liver blood test abnormality is not necessarily a guide to clinical significance. This is determined by the specific analyte which is abnormal (outside the reference range) and the clinical context.

Duration of Abnormality and Retesting

- Patients with abnormal liver blood tests should be considered for investigation with a liver aetiology screen irrespective of level and duration of abnormality. Abnormal refers to an analyte which is outside the laboratory reference range.

Clinical Pattern Recognition for Liver Blood Tests

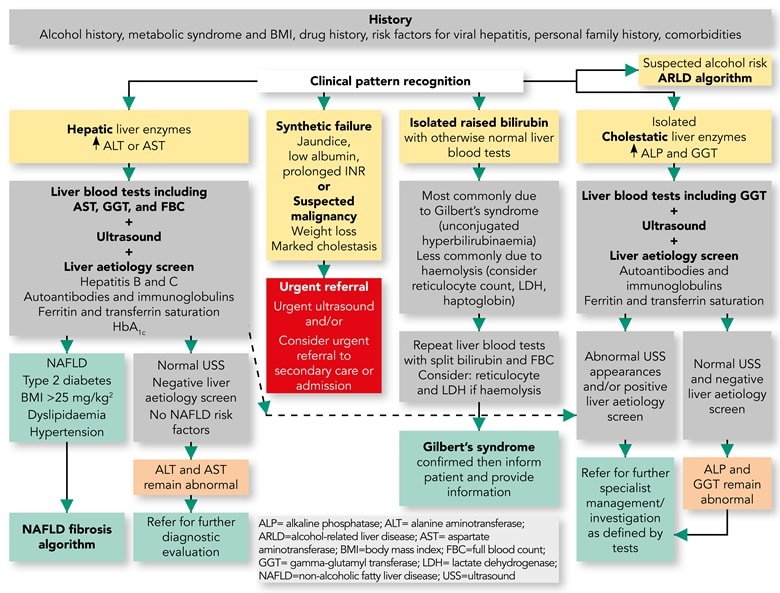

Figure 1: Response to Abnormal Liver Blood Tests

Response to Abnormal Liver Blood Tests: Outcomes and Pathways

- As indicated in Figure 1, the presence of unexplained clinical jaundice or suspicion of possible hepatic or biliary malignancy should lead to an immediate referral

- In all other adults with incidentally raised liver enzymes it is important to take a careful history and perform a targeted clinical examination to look for the cause

- In adults a standard liver aetiology screen should include abdominal ultrasound scan (USS), hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C antibody (with follow-on polymerase chain reaction if positive), anti-mitochondrial antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, antinuclear antibody, serum immunoglobulins, simultaneous serum ferritin and transferrin saturation

- In children, ferritin and transferrin saturation may not be indicated, but autoantibody panel should include anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody and coeliac antibodies. Alpha-1-antitrypsin level and caeruloplasmin (age >3 years) should be included, and abnormalities discussed with an appropriate inherited metabolic disease specialist.

Approach to Common Conditions

NAFLD

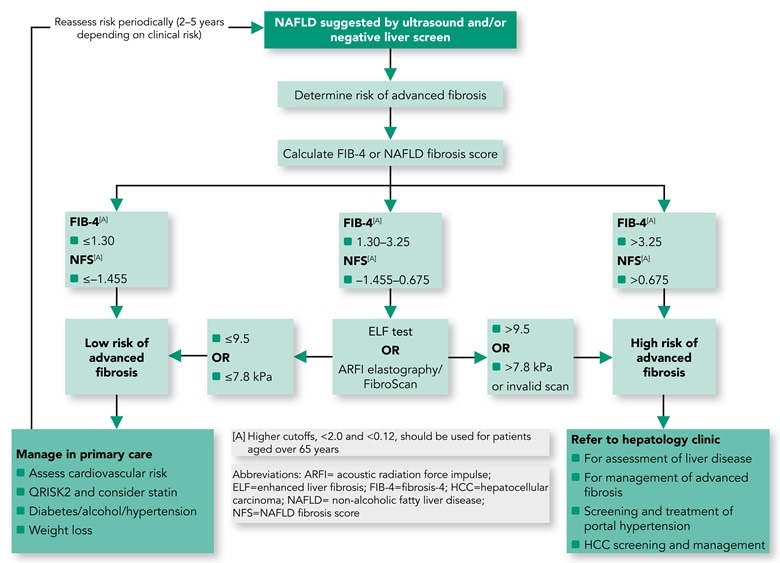

Figure 2: Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Fibrosis

- Adults with NAFLD should undergo risk stratification to determine their extent of liver fibrosis.

- first-line testing should use either FIB-4 or NAFLD Fibrosis Score. Calculation facilities for FIB-4 and NFS should be incorporated in all primary care computer systems.

- second-line testing requires a quantitative assessment of fibrosis with tests such as serum ELF measurements or Fibroscan/ARFI elastography

- hepatologists at a local level should champion this idea and discuss it with commissioners of health to deal with the burden of liver disease in their area (Figures 1 and 2).

ARLD

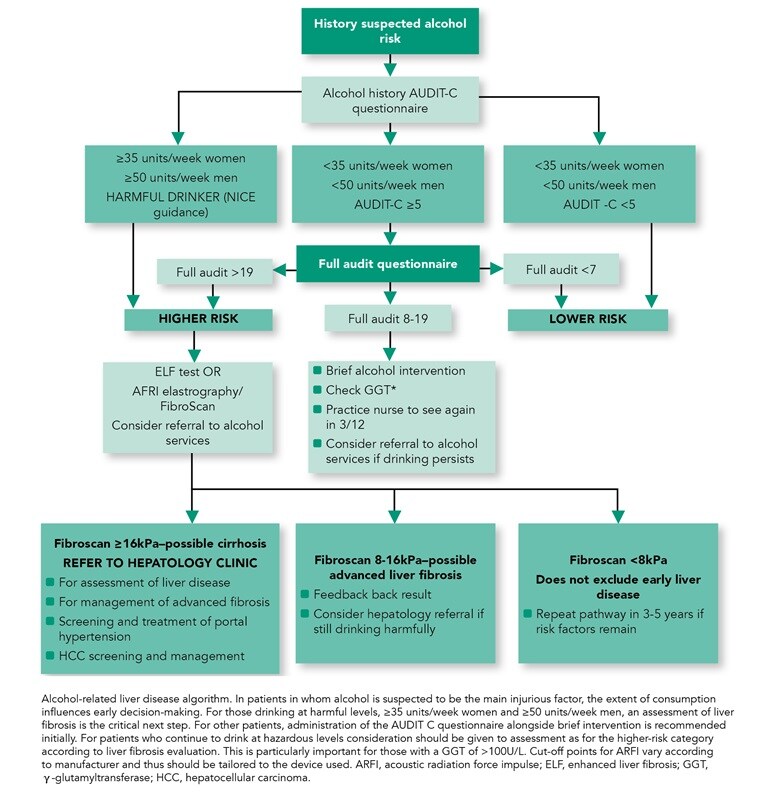

Figure 3: Alcohol-related Liver Disease

- Consider referral to alcohol services for all adults with alcohol-related liver disease (ARLD) with evidence of alcohol dependency as defined by an AUDIT score of >19

- Harmful drinkers should undergo risk stratification with clinical assessment and Fibroscan/ARFI elastography. Adults should be referred to secondary care if there is evidence of advanced liver disease (features of cirrhosis or portal hypertension on imaging or from blood tests) and/or Fibroscan reading is >16 kPa (if available).

Approach to a Patient with Abnormal Liver Blood Tests and a Negative Extended Liver Aetiology Screen

- When the extended liver aetiology screen is negative (Table 1), including an abdominal USS, it is important to re-examine the history to exclude potential drug-induced aetiologies, including over-the-counter preparations and any potential recreational/herbal drug use

- Adults with abnormal liver blood tests, even with a negative extended liver aetiology screen and no risk factors for NAFLD, should be referred/discussed to a gastroenterologist with an interest in liver disease/hepatologist for further evaluation (Figure 1).