Overview

This Guidelines summary covers key recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of insomnia, parasomnia, and circadian rhythm disorders relevant to primary care. Please see the full guideline for the complete set of recommendations.

Diagnostic Criteria of Insomnia

Table 1: Insomnia—Diagnostic Criteria

| Classification | Criteria | Occurrence | Other Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) and (Sateia et al. 2017) | A The patient reports (or the patient’s parent or caregiver reports) marked concern about, or dissatisfaction with, sleep comprising one or more of the following:-difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, waking up earlier than desired, resistance in going to bed on the appropriate schedule, difficulty sleeping without the parent or caregiver present. | B Occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep. | C At least one form of daytime impairment e.g. fatigue; mood disturbance; interpersonal problems; reduced cognitive function; reduced performance; daytime sleepiness; behavioural problems (e.g. hyperactivity, impulsivity, aggression); reduced motivation/initiative; proneness to errors/accidents. |

| International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10; World Health Organization, 1992 | Difficulty falling asleep, - maintaining sleep or - non-refreshing sleep. | Three times a week and for longer than one month. | Marked personal distress or interference with personal functioning in daily living. |

| Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; insomnia disorder) | Unhappiness with the quality or quantity of sleep, which can include trouble falling asleep, staying asleep or waking up early and being unable to get back to sleep. The problem occurs despite ample opportunity to sleep. The difficulty cannot be better explained by other physical, mental or sleep-wake disorders. The problem cannot be attributed to substance use or medication. | Three nights a week for at least three months. | The sleep disturbance causes significant distress or impairment in functioning, such as within the individual’s working or personal life, behaviourally or emotionally. |

| Diagnostic criteria from the American Psychiatric Association, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, and World Health Organization | |||

Diagnosis of Insomnia

- Like depression, anxiety or pain, there is no objective test for insomnia, and in practice it is evaluated clinically. Diagnosis, therefore, is through appraisal against diagnostic criteria, clinical observations and the use of validated rating scales.

- The simplest way in which sleep can be assessed is by asking the patient about their sleep. Are they having difficulty getting to sleep and/or staying asleep? Is this occurring most nights? Is this persistent and affecting how they feel during the day?

- An extension of this interview enquiry is to administer a clinical rating scale. The Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI) is one such scale being based on contemporary diagnostic criteria and has been validated in over 200,000 adults. It also has a short-form screening version comprising only two items.

- Some patients appreciate completing a diary to capture the nature of their sleep problems, including the unpredictability of their sleep from night to night. The SCI and the diary may also be useful to assess treatment-related change.

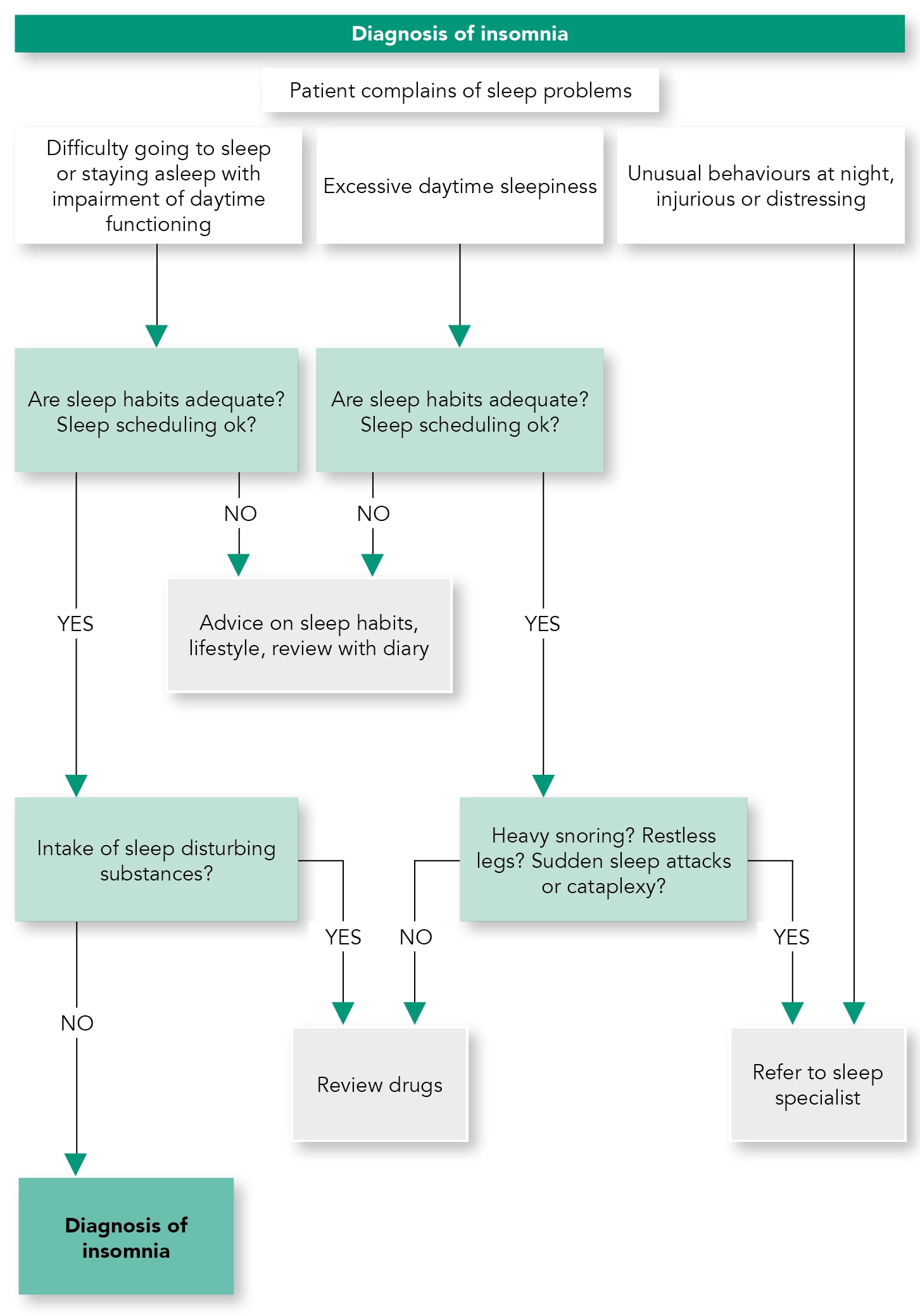

- It is important to determine if another sleep disorder (see preliminary questions below), or a physical (such as pain, heart or metabolic disease), neurological (such as Parkinson’s disease or cerebrovascular disease) or psychiatric disorder (such as depressive illness, anxiety disorder or substance use disorder) is present along side the insomnia. The insomnia problem should be actively treated, but consideration of the interplay between conditions is good clinical practice. A diagram illustrating diagnosis is given in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1: Diagnosis of Insomnia

| Box 1: Asking About Another Sleep Disorder—Preliminary Questions |

|---|

|

Treatment of Insomnia

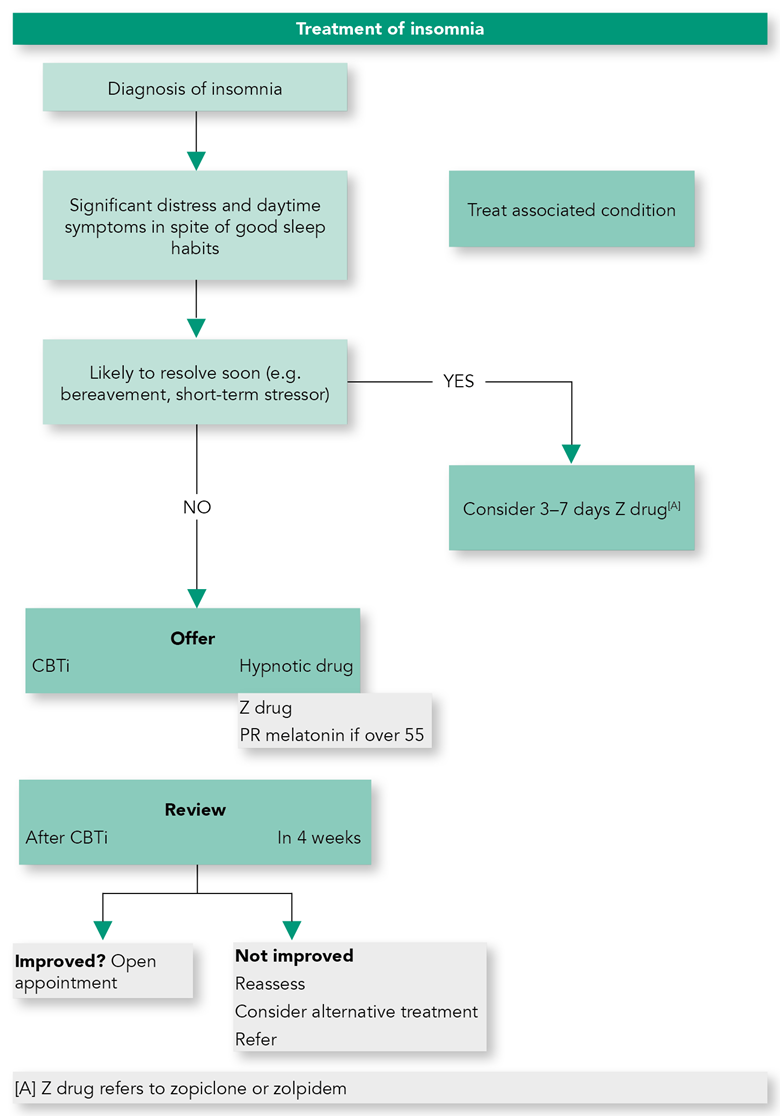

Algorithm 2: Treatment of Insomnia

- It is important to treat insomnia because the condition causes decreased quality of life, is associated with impaired functioning in many areas, and leads to increased risk of depression, anxiety and possibly diabetes and cardiovascular disorders.

- Cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi) should be offered as first line treatment.

- In case of treatment failure, unavailability of CBTi, or inability to engage with CBTi, pharmacological treatment with an evidence base should be offered (see Algorithm 2).

- CBT-based treatment packages for chronic insomnia including sleep restriction and stimulus control are effective and therefore should be offered to patients as a first-line treatment.

- Both face to face CBTi and digital cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia (dCBTi) are efficacious. dCBTi has the potential to offer patients and clinicians a choice amongst evidence-based alternatives (CBT or drugs) in routine clinical care.

Drug Treatments for Insomnia

- Factors which clinicians need to take into account when prescribing are:

- efficacy

- safety

- duration of action.

- Other factors are:

- previous efficacy of the drug or adverse effects

- history of substance abuse or dependence.

Long-term Use of Sleeping Medications

- Use as clinically indicated.

- In general, hypnotic discontinuation should be based on slowly tapering off medication.

- CBTi during taper improves outcome.

Using Drugs for Depression to Treat Insomnia

- Use drugs according to a knowledge of pharmacology.

- Consider drugs for depression when there is co-existent mood disorder.

- Beware toxicity of tricyclic antidepressants in overdose even when low unit doses prescribed.

Drugs for Psychosis for Treatment of Insomnia

- Side effects are common because of the pharmacological actions of drugs for psychosis and there are a few reports of abuse. Together these indicate no indication for use as first-line treatment.

Antihistamines (H1 Antagonists)

- The selective antihistamine doxepin (very low dose) is effective in insomnia.

- Non-selective histamine antagonists have a limited role in psychiatric and primary care practice for the management of insomnia.

Circadian Rhythm Disorders

- Daily rhythms of sleeping and waking are controlled by a variety of brain mechanisms, the most prominent of these being the circadian process (the ‘body clock’ signalling time for sleep) and the homeostatic process (a build-up of sleep pressure during the hours of wakefulness). These two processes work together to consolidate sleep and wakefulness.

- Circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders (CRSWDs) occur when there is an alteration of the endogenous circadian system or a misalignment between the endogenous circadian rhythm and the sleep-wake schedule required by the physical environment or social or work timetable. This results in insomnia when they are needing to sleep, and sleepiness when alertness is required, causing significant distress and impairment of function.

Diagnosis of Circadian Rhythm Disorders

- Assessment of these disorders involves interview, sleep diaries (from parents/carers if necessary) and actigraphy for 14 days. In the case of delayed sleep-wake phase disorder and advanced sleep-wake phase disorder it is recommended to give the morningness-eveningness questionnaire.

Treating Circadian Rhythm Disorders

- Clinical assessment is essential in delayed sleep wake phase disorder, non-24-hour sleep rhythm disorder.

- Melatonin may be useful in delayed sleep wake phase disorder, non-24-hour sleep rhythm disorder in non-sighted individuals and jet lag disorder.

- Other approaches such as behavioural regimes and scheduled light exposure (in sighted individuals) can also be used.

- Because of the necessity for careful timing of interventions, patients with these disorders need to be treated in specialised sleep disorders centres.

Parasomnias

- Parasomnias are unusual episodes or behaviours occurring during sleep that disturb the patient or others. This summary addresses those that cause significant distress and therefore pre sent for treatment. Violent or unusual night-time attacks may arise from deep non-REM sleep (night terrors and sleepwalking) or from REM sleep [sleep paralysis, severe recurrent nightmares, REM behaviour disorder(RBD)] and treatments depend on which disorder is present.

Diagnosis of Parasomnias

- Assessment of parasomnia may be possible with a detailed history from patient or witness, but in general for adequate diagnosis, referral to a specialist sleep centre for polysomnography and video recording may be necessary especially for RBD where loss of REM atonia is seen.

Treatment of Parasomnias

- There is little high-level evidence for treatments in these disorders. Priorities are to minimise possible trigger factors such as noise, frightening films, caffeine, alcohol or meals late at night; and to make sure there is a stable and adequate sleep-wake schedule. It is important to safeguard against harm to the patient, such as by locking windows, bolting doors, or sleeping on the ground floor, and safety of the bed partner or nearby children also requires attention.

Special Populations

Menopause

- Insomnia increases as women approach and pass through the menopause.

- Clinicians should appreciate that there is a rise in incidence of sleep-disordered breathing after the menopause and that clinical presentation, often including insomnia, in women is different to men.

- The use of hormone therapy should involve informed individualised treatment of symptoms, looking at risks and benefits in light of recent studies.

- Follow recommendations for insomnia in other sections.

Pregnancy

- Many women report poor sleep during pregnancy with the reasons varying depending on the trimester.

- Encourage good sleep hygiene and lifestyle.

- Manage general pregnancy associated complaints, e.g. decrease fluid intake, pillow support.

- The effects of CBTi in pregnancy have only been assessed in one small open-label study, but this approach seems sensible.

- Recognise RLS by careful history and investigations if necessary.

- Dopamine agonists are contraindicated (FDA category C or greater)

- Iron supplementation has been shown to be effective in RLS. Supplementation is suggested even if levels are not low

- Keep caffeine low as it can exacerbate RLS

- Mild-moderate exercise in the early evening, stretching, massage.

- If patient suffers from intractable insomnia and a pharmacological agent is required, zolpidem or zopiclone should be used short term after discussion on potential risks and benefits.

Treatment of Insomnia in Older Adults

- CBTi is effective and should be offered as a first-line treatment where available.

- When a hypnotic is indicated in patients over 55 years prolonged release melatonin should be tried first.

- If a GABA-A hypnotic is used then a shorter half-life will minimise unwanted hangover effects.

Sleep Problems in Children

- Behavioural strategies should be tried first in children with disturbed sleep.

- Melatonin improves sleep in children with ASDs.

- Melatonin administration can be used to advance sleep onset to normal values in children with ADHD who are not on stimulant medication.

Sleep Disturbance in Adults with Intellectual Disability

- Clinical assessment should describe sleep disturbance and elicit aetiological and exacerbating factors.

- Environmental, behavioural and educational approaches should be used first line.

- Melatonin is effective in improving sleep.

- Treatment should be planned within a capacity/best interests framework.