Latest Guidance Updates:03 July 2023: added recommendation on referral to secondary care if squamous cell carcinoma is a differential diagnosis, in the section Investigations. |

Overview

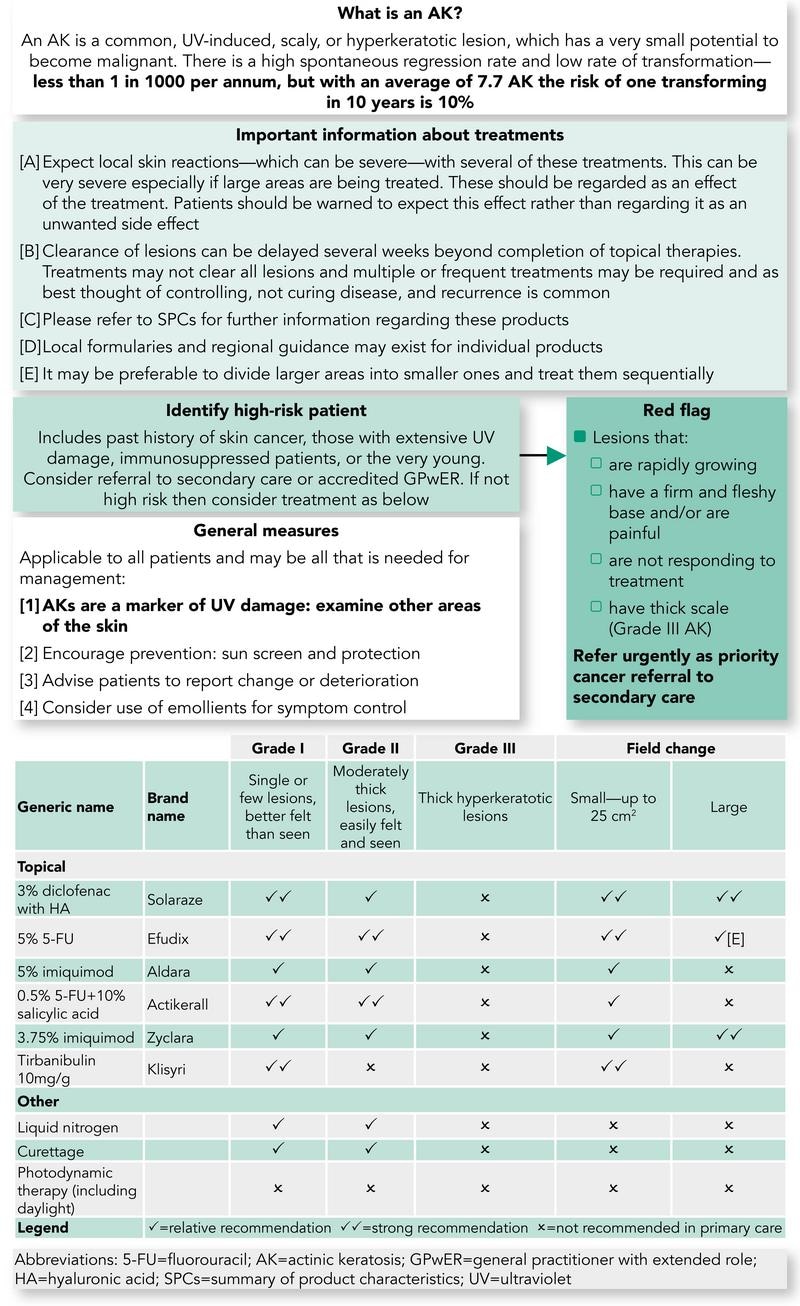

This Guidelines summary on actinic keratosis (AK; also termed solar keratosis) includes recommendations on aetiology, history, use of clinical findings, investigations, management, and options for treatment. It includes an algorithm of the pathway from recognition to treatment in primary care, including red flags to recognise.

Reflecting on your Learnings

Reflection is important for continuous learning and development, and a critical part of the revalidation process for UK healthcare professionals. Click here to access the Guidelines Reflection Record.

Introduction

- An actinic keratosis (AK) is a common, sun-induced, scaly or hyperkeratotic lesion, which has the potential to become malignant. NICE estimates that over 23% of the UK population aged 60 years and above have an AK. Although the risk of an AK transforming into a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is very low, this risk increases over time and with larger numbers of lesions. The presence of 10 AKs is associated with a 14% risk of developing an SCC within 5 years.

Aetiology

- AKs are a consequence of cumulative long-term sun-exposure:

- lesions are very uncommon under the age of 45 years

- the incidence increases with age

- the exceptions are patients with xeroderma pigmentosum and albinism, who can develop AKs at a very young age

- Genetic factors play a role and individuals with fair skin, blue eyes, and blonde hair are at higher risk, whereas lesions are exceedingly rare in patients of skin types IV–VI

- Artificial ultraviolet radiation, such as ultraviolet B and psoralen and ultraviolet used to treat psoriasis and a number of other skin conditions—as well as the use of sun beds—increase the risk

- Men are affected more often than women.

History

- Lesions are normally asymptomatic

- Recent growth, pain/tenderness, bleeding, or ulceration are suggestive of transformation into an SCC.

Clinical Findings

Distribution

- Reflects the intensity of sun exposure with the greatest number of lesions occurring on the head, neck, forearms, and hands

- There is often a background of significant sun-damaged skin with pigment irregularity, telangiectasia, erythema, and collagenosis (a yellow papularity of the skin).

Morphology

- Lesions usually take on a similar appearance and seldom exceed more than 1 cm in diameter

- Rough surface scale—usually white, although in patients with skin type I, AKs are often more easily felt than seen

- Often referred to as flat, although some lesions can have significant amounts of scale (hypertrophic or bowenoid AK), which may be elevated.

Dermoscopic Features

- White-yellow scale

- A red pseudonetwork giving a strawberry-like appearance

- Occasionally 'rosette-like' structures, comprised of four grouped dots/globules (clods), best seen under polarised light

- Structures may not be visible if there is a lot of scale.

AK Variants

- Actinic cheilitis—these are actinic keratoses affecting the lips

- Pigmented—small triangular areas of brown scale may be seen dermoscopically. The differential diagnosis includes lentigo maligna

- Lichenoid—smooth and shiny, mainly occurring in areas of friction.

Investigations

- Diagnosis is usually clinical. If a diagnostic biopsy is required, the primary histologic feature is partial thickness atypia/dysplasia of the keratinocytes in the basal layers of the epidermis. This is often accompanied by parakeratosis, thinning of the granular layer, buds of atypical epidermis extending toward the papillary dermis, dermal solar elastosis, and inflammation

- If SCC is a differential, the patient must be referred urgently to secondary care without a biopsy.

Management

Who Should Manage AK?

- The majority can be managed in general practice. The following groups should be referred:

- to a GP with an extended role/accredited GP with a special interest or dermatologist

- diagnostic uncertainty

- patients with more widespread/severe actinic damage

- if an SCC is suspected, refer to secondary care as urgent. The following could suggest transformation from an AK into an SCC:

- history—recent growth/pain/bleeding

- examination—an elevated lesion (if significant surface scale, remove to see if there is a palpable lump underneath), ulceration, induration, tenderness, and surrounding inflammation

- beware lesions on lips—SCC can be very subtle at this site

- have a low threshold for referring immunosuppressed patients (in particular post-transplant) who are at high risk of developing SCC that tend to metastasise quicker

- very young patients presenting with AK—consider xeroderma pigmentosum.

- to a GP with an extended role/accredited GP with a special interest or dermatologist

Treatment of AK

Step 1: General Measures—Appropriate For All Patients

- AKs are a marker of sun damage and so a thorough skin examination is needed to look for more serious sun-related skin tumours, such as melanoma

- Moisturisers—it can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between early AK and dry, scaly areas of normal skin. The use of a moisturiser two to three times a day can be helpful in differentiating between areas of normal and abnormal skin

- The PCDS patient information leaflet provides the patient with all necessary information, including a place for the health professional to provide treatment notes, advice on ultraviolet protection and vitamin D, self-management of AK, and links regarding self-examination.

Step 2: Observation

- Not all patients need treating, for example, patients with smaller numbers of lesions, especially if they have a reduced life expectancy—such patients should be given a choice of whether or not they wish to have their lesions treated.

Step 3: Lesion Specific Treatment—a Few Lesions or Larger Numbers That Are Widely Distributed (For Example, Dotted Around the Face, Scalp, and Hands)

- Treat the individual lesions and not the normal surrounding skin. Options are:

- fluorouracil 5% cream—apply every night for 4 weeks. Wash hands thoroughly after application. Leave treated areas uncovered and wash the following morning. Patients should be advised to expect redness, crusting, and some discomfort during treatment

- tirbanibulin—apply once a day for 5 days. Patients should be advised to expect redness, crusting, and some discomfort during treatment

- 0.5% fluorouracil/10% salicylic acid solution is also suitable for treating moderately thick (hyperkeratotic) AK—it should be used once a day for 6–12 weeks. The solution tends to leave a film on the skin, which should be washed/peeled off before the next application

- cryotherapy—a single freeze–thaw cycle of approximately 10 seconds (avoid the gaiter area of the legs because of risk of leg ulceration, and warn patients if used on the face it can cause hypopigmentation).

Step 4: Field Change

- Field change refers to areas of skin that have multiple AKs associated with a background of erythema, telangiectasia, and other changes seen in sun-damaged skin. These areas are probably more at risk of developing SCC, especially if left untreated and, as such, it is recommended that they should be treated more vigorously. The treatments should be applied to the whole area of field change and not just the individual lesions

- As when treating other patients with AK, the primary aim of treatment is to reduce the total number of lesions that the patient has at any one time; the fewer lesions a patient has, the less risk they have for developing an SCC. Treatment courses will need to be repeated from time to time. Note that all field-based treatments will elicit local skin responses, which are expected as part of the treatment. The length of time a patient has to endure local skin responses varies widely between the treatments referred to below, and this needs to be discussed with the patient to aid them with decision making

- For smaller areas of field change (for example, an area the size of a palm or most of the forehead), consider the following treatments, which are listed in no particular order:

- 5% imiquimod cream

- use three nights a week, for example, Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, for 4 weeks. Apply overnight and wash off the following morning. After 4 weeks, stop the treatment and consider the use of a mild topical steroid, for example, 1% hydrocortisone or clobetasone butyrate cream twice daily for 2–4 weeks, to help settle down any inflammation. Follow up 3 months after the treatment was started, and repeat the treatment if needed

- advantages—generally very effective in terms of clearance and cosmetic appearance once inflammation resolved

- disadvantages—patients should be warned to expect marked erythema with crusting of the skin. Timing of the treatment is important and it is best avoided during holidays and important social occasions. Some patients develop flu-like symptoms during treatment

- fluorouracil 5% cream

- used once a day for 4 weeks. Apply thinly in an evening with a gloved finger; alternatively, wash the finger after application. The treated area should be washed the following morning. After 4 weeks, stop the treatment and consider the use of a mild topical steroid, for example, 1% hydrocortisone or clobetasone butyrate cream twice daily for 2–4 weeks, to help settle down any inflammation. Follow up 3 months after the treatment was started

- advantages and disadvantages are similar to with imiquimod cream, although patients do not develop flu-like symptoms

- tirbanibulin

- used once a day for 5 days. Patients should be advised to expect redness, crusting, and some discomfort during treatment

- 0.5% fluorouracil/10% salicylic acid solution

- used once a day for 6–12 weeks. The solution tends to leave a film on the skin, which should be washed/peeled off before the next application

- photodynamic therapy

- this is provided by some dermatology departments and occasionally GPwER clinics

- a single treatment often provides an effective treatment for an area of field change. The skin settles down within a few days of treatment. Cosmetic outcomes are good

- 5% imiquimod cream

- For larger areas of field change consider the following treatments (listed alphabetically):

- 3% diclofenac gel

- use twice a day for 8–12 weeks. Review patient 4 weeks after treatment has finished to assess response

- advantages—generally well tolerated and so can be used on any sized area

- disadvantages—most dermatologists view diclofenac gel as a milder treatment, which may not be as effective as some of the other treatments and so it is best used where the AK are thin. Once treatment is complete, any remaining AK can then be managed with the treatments referred to in step 3 above

- 3.75% imiquimod cream

- apply once daily for 2 weeks, followed by a 2-week treatment-free period, and then a further once daily application for 2 weeks (that is, 6 weeks in total, but only 4 weeks of treatment)

- adverse effects less than when using 5% imiquimod cream.

- 3% diclofenac gel

Erosive Pustular Dermatosis of the Scalp

- Is an uncommon condition affecting ultraviolet-damaged areas of the scalp in older patients. The risk appears to be increased with the subsequent treatment of AK, especially with cryotherapy

- Clinically, there are varying degrees of scarring associated with yellow-brown crusts, pustules, lakes of pus, erosions, and ulceration

- The primary treatment is the use of super-potent topical steroids.

AK Treatment Pathway

Algorithm 1: AK Treatment Pathway