Latest Guidance UpdatesMarch 2024: updated inhaler options in 'Licensed for MART' table. Refer to the full guideline for this information. February 2024: updated to include a new ‘preferred regimen’ for mild asthma, and the option to use some asthma medicines in an unlicensed manner was added. These updates were to bring the guidance in line with other nationally recognised recommendations. |

Overview

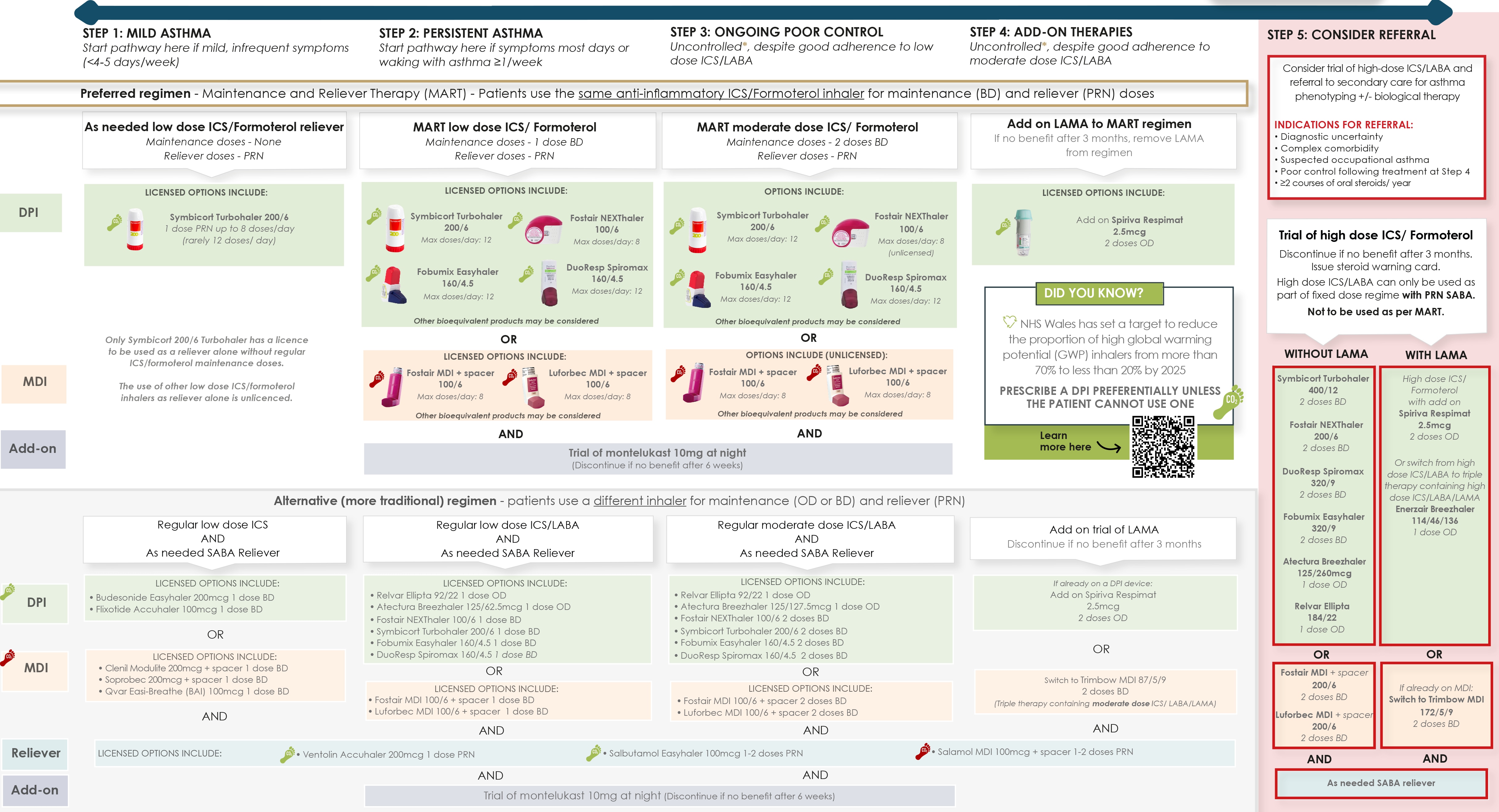

This Guidelines summary of the All Wales Medicines Strategy Group’s adult asthma management and prescribing guideline encompasses core principles of asthma management, inhaler selection and use, and referral guidance.

Reflecting on Your Learnings

Reflection is important for continuous learning and development, and a critical part of the revalidation process for UK healthcare professionals. Click here to access the Guidelines Reflection Record.

Key Principles

Core Principles

- Perform objective tests to confirm a suspected diagnosis of asthma

- All patients should be treated with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)

- The preferred regimen is a regular ICS/formoterol-containing inhaler, with as-needed doses of the same inhaler taken in response to symptoms (maintenance and reliever therapy [MART])

- In mild asthma with infrequent symptoms, ICS/formoterol can now be used on an as-needed basis (pro re nata [PRN]), without regular maintenance dosing. This anti-inflammatory reliever (AIR) approach reduces the risk of exacerbations and unscheduled healthcare attendances compared with a daily ICS and PRN short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA)

- An alternative regimen is provided. Consider if a patient is stable, with good adherence, infrequent use of SABA (<3 per year), and no exacerbations in the last year on their current therapy. If a patient's asthma is poorly controlled, they should be switched to the preferred regimen

- Ensure that the patient's asthma action plan is updated.

Inhaler Principles

- Choice of inhaler is based on patient’s preference and technique (use in-check device to assess inspiratory effort)

- Whenever possible, choose a device with low global warming potential

- If more than one inhaler is being prescribed, ensure that these use the same technique (that is, do not mix metered-dose inhalers [MDIs] and dry-powder inhalers [DPIs])

- ICS and long-acting beta2 agonists (LABA) must be prescribed as a combination product to obviate the risk of patients taking LABA monotherapy (associated with increased risk of mortality)

- MDIs should be used with a spacer device

- Prescribe by brand and specify device (for example, Fostair NEXThaler)

- At step 3, Fostair and Luforbec are unlicensed options. See page 7 of the supporting notes in the full guideline for further information.

Asthma Control

- Good control is defined as no daytime symptoms, no night-time waking, no limitations in activity, and no exacerbations

- Before stepping up therapy, confirm symptoms are due to asthma, and address inhaler technique, adherence, and comorbidity

- Consider stepping down treatment if control is good for 3 months.

Exacerbation/Emergency Treatment

- Administer up to six doses of ICS/formoterol at 1-minute intervals. Do not go back to SABA therapy

- If symptoms persist, seek urgent medical advice.

Prescribing Guidance

Algorithm 1: Prescribing Guidance

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of asthma is a clinical diagnosis supported by tests of airway hyper-responsiveness and airway inflammation. All patients with suspected asthma should undergo objective testing including spirometry/reversibility and peak flow diary monitoring to document evidence of variable airflow obstruction

- Exhaled nitric oxide (where available) is a simple breath test that can identify airway inflammation that is likely to respond to ICS. An elevated fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) level is supportive (but not diagnostic) of asthma

- It should be usual practice to perform objective testing prior to starting therapy for asthma. If inhalers have already been prescribed, these will need to be withheld prior to performing bronchodilator reversibility testing

- Most ICS/LABA will need to be withheld for more than 12 hours; however, once daily preparations (for example, Relvar) will need to be withheld for more than 24 hours

- SABA need to be withheld for more than 4 hours and long-acting anti-muscarinic agents (LAMA) for more than 36 hours

- Inhalers do not need to be withheld prior to performing FeNO; however, levels of FeNO will be reduced by ICS. Ideally, objective tests should be performed prior to starting inhaled therapy

- Reversibility to either inhaled or oral corticosteroids could also be considered if initial spirometry is obstructive (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC] ratio less than 0.7 or below lower limit of normal). A change in FEV1 of more than 12% and 200 ml confirms reversibility and supports an asthma diagnosis

- Some patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) also show reversibility, and asthma and COPD can coexist (asthma–COPD overlap syndrome)

- Clinical history is important in distinguishing asthma from COPD

- When diagnostic uncertainty remains, or both COPD and asthma are present, use the following findings to help identify asthma:

- a large (over 400 ml) response to bronchodilators

- a large (over 400 ml) response to 30 mg oral prednisolone daily for 2 weeks

- serial peak flow measurements showing 20% or greater diurnal or day-to-day variability

- Clinically significant COPD is not present if the FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio return to normal with drug therapy.

General Principles of Management

- The aims of asthma management are to achieve good symptom control and to minimise the future risk of asthma exacerbations, mortality, persistent airflow obstruction, and side effects of treatment

- Recent guidelines (British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [BTS/SIGN] and NICE [diagnosis and monitoring, and chronic asthma management]) have highlighted the need to treat all individuals symptomatic of asthma with ICS

- The practice of using a short-acting bronchodilator as monotherapy is now outdated and reports such as the National Review of Asthma Deaths have highlighted the potential dangers of this practice, with underuse of ICS and overreliance on beta2 agonists a contributory factor in a number of deaths

- For individuals with mild, intermittent asthma, there is now good evidence for the use of ICS/formoterol on a PRN basis in response to symptoms (no need for maintenance therapy). This is referred to as AIR therapy

- Symbicort Turbohaler 200/6 is the first inhaler to receive a licence from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency for use in this way (in addition to its role as a preventer and MART). The evidence supporting this approach is with low-dose budesonide-formoterol

- Other ICS-formoterol preparations have not been studied, but the use of beclomethasone-formoterol is now the preferred option for individuals with mild asthma (defined as symptoms on fewer than 4–5 days per week)

- The use of PRN ICS/formoterol in this way allows patients to titrate the dose of inhaler to their symptoms. It is important that patients do not revert back to their SABA inhaler during exacerbations, as this is when the anti-inflammatory effect of the ICS/formoterol is most beneficial

- For individuals with persistent asthma, the use of a regular, maintenance formoterol containing ICS/LABA, with the same inhaler used as a reliever, is the preferred option. This MART approach has been shown to reduce exacerbations compared to conventional asthma treatments (see later section on MART)

- An alternative regimen is provided. For those patients who are very stable on their current preventer inhalers, with good adherence, no exacerbations, and rare use of SABA (<3 SABA inhalers a year), there is no need to change management. If the patient's asthma is poorly controlled, or they experience exacerbations on the traditional regimen, they should be switched to the preferred regimen. This will usually be done at the same treatment step, but in very poor control, a step up may be required. If a patient with well-controlled asthma wishes to switch to the preferred regimen (for example, for simplicity of single inhaler), they can be switched at the same treatment step.

Asthma Control

- An objective measure of asthma control and risk of adverse outcomes should be recorded during each consultation. This would usually include a symptom score, such as the ‘asthma control test’ or the Royal College of Physicians’ ‘three questions’, a measure of airflow obstruction (peak flow or spirometry), and an assessment of exacerbation risk and symptoms based on ICS adherence, reliever use, and any requirement for oral steroids

- Reliever inhalers should not be required more than twice per week. The risk of severe exacerbations and mortality increases incrementally with higher SABA use, independent of treatment step. Prescribing three or more 200-dose SABA inhalers per year, corresponding to daily use, is associated with an increased risk of severe exacerbations and mortality and reflects very poorly controlled asthma

- For those patients using AIR therapy (or MART), each extra dose taken provides additional controller medication, and so helps to prevent exacerbations. The cut-off of more than two doses of reliever therapy a week (indicating poor control) does not therefore apply for the preferred regimen

- The average frequency of reliever doses of ICS/formoterol over a 4-week period should be considered. If persistent rescue doses beyond the maintenance dose are required (as a guide, more than seven per week), this should be considered when reviewing the necessary maintenance dose and need for add-on therapy.

Table 1: Levels of Asthma Control and Exacerbation Risk

Assessment of Current Clinical Control (Over Last 4 Weeks)

| Characteristic | Completely Controlled | Partly Controlled | Uncontrolled |

| Daytime symptoms more than twice per week | None of these | 1–2 of these | 3–4 of these |

| Limitation on activities | |||

| Nocturnal symptoms/awakening | |||

| SABA reliever more than twice per week (if on traditional regimen) | |||

| Asthma control test | 21–25 well controlled | 16–20 poorly controlled | 0–15 very poorly controlled |

| Additional risk factors for future exacerbation | |||

| Previous exacerbation/asthma attack | Especially within the last 12 months Intubation/intensive care admission (ever) | ||

| Medication adherence | Increased risk if poor ICS adherence (<80%), poor inhaler technique, and high SABA use (increased risk of exacerbation if ≥3 SABA/year and mortality if more than one SABA inhaler/month) | ||

| Lung function (peak flow or FEV1) | Increased risk if reduced lung function, especially if <60% predicted | ||

| Comorbidities | Smoking, obesity, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, pregnancy, chronic rhinosinusitis, anxiety, depression, confirmed food allergy, socioeconomic problems | ||

| Type 2 inflammatory biomarkers | Higher eosinophils and FeNO | ||

| ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; SABA=short-acting bronchodilator; FeNO=fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1 =forced expiratory volume in 1 second. | |||

Device Selection

- Always involve the patient when choosing the device. Take into account individual preference, ease at which the device can be used, and prior success or failure with different preparations, as well as the environmental impact of the inhaler

- Ensure continuity of device for individual patients so that only one inhaler technique is required. Whenever possible do not mix MDIs and DPIs as they require radically different inhaler techniques (slow and gentle versus forceful and deep)

- A patient decision aid has been produced by NICE that may be useful in guiding device selection. MDIs have a higher carbon footprint than DPI devices and BTS guidelines recommend that inhalers with low global-warming potential should be used when they are likely to be equally effective

- MDIs currently contribute an estimated 3.5% of the carbon footprint of the NHS. MDIs comprise 70% of all inhalers prescibed in the UK, but only 14% in Sweden. The default option should be to prescribe a DPI, unless a patient has a better technique, or prefers, an MDI. Patients should also be encouraged to use any locally available inhaler recycling and recovery schemes. Patients can return empty inhalers to their community pharmacy

- Ventolin (salbutamol) MDI has been omitted from the guidelines as it is an MDI with a very high carbon footprint (>25 kg carbon dioxide equivalent [CO2e] per inhaler). Salamol in comparison has a lower carbon footprint (<10 kg CO2e per inhaler), although is still classed as a high global warming potential inhaler in comparison to DPIs

- DPIs require inspiratory flow rates of 30–90 l/min. The In-Check DIAL device or training whistles should be used to check that patients can achieve this

- MDIs should be used with a spacer device (Aerochamber flow-vu or Volumatic) to improve technique and lung deposition. The Flo-Tone device is also useful to optimise MDI technique

- It is important to teach patients that they need to wait 30 seconds between activations of their MDI devices to allow time for the canister to recharge before administering a second dose

- Full instruction on the inhaler technique for specific devices can be found on the Right-Breathe app or asthma UK website. The NHS AsthmaHub app contains educational videos on inhaler technique

- ICSs and long-acting bronchodilators MUST be prescribed as a combination product to obviate the risk of patients inadvertently taking the LABA as monotherapy, which has been associated with increased risk of mortality

- All inhalers should be prescribed by brand to prevent the wrong inhaler device being inadvertently issued by the pharmacy

- When there is a choice of inhalers, the lowest-cost item should be preferred. An increasing number of bioequivalent inhalers are coming to market. These can be considered but will involve a

face-to-face review with the patient to explain differences in how to use the device.

Stepping Up Therapy

- It is important to check and address factors known to be associated with poor asthma control at every opportunity, including when considering a step up in treatment. The following factors should be considered:

- diagnosis—is there good evidence for the asthma diagnosis?

- inhaler technique

- adherence with asthma medication. This can be checked by an open conversation with the patient—it is important to be non-judgemental and explore barriers to adherence with medication (for example, dislike of device, side effects, chaotic lifestyle). The prescription ‘fill rate’ should be reviewed (that is, the actual number of preventative inhalers collected [issued] in a 12-month period compared with the number that should have been collected [issued]). This is a surrogate measure of adherence and can prompt a conversation with a patient

- smoking status (including vaping) and referral to smoking-cessation services

- triggers and trigger avoidance (including occupation)

- comorbid conditions—for example, weight management, obstructive sleep apnoea, dysfunctional breathing pattern, rhinitis

- Asthma control should be reassessed within 3 months of a change in therapy.

Maintenance and Reliever Therapy

- A number of combination inhalers are licensed for use in a variable dosing regimen, termed MART. These include Fostair 100/6 MDI and NEXThaler, Symbicort 200/6 Turbohaler, Fobumix 160/4.5, and Duoresp Spiromax 160/4.5

- Higher-strength preparations are not licensed for this use

- The patient should take twice-daily maintenance therapy and then also use the same product and device as a reliever medication if required. This enables the amount of inhaled steroid to be titrated against symptoms

- Do not prescribe a separate reliever inhaler if a patient is on this regimen.

Add-on Therapies

Montelukast

- Montelukast can be trialled at step 2 or 3 of the treatment pathway, dependent on patient phenotype and choice. It may be particularly helpful in those with exercise-induced asthma, aspirin-exacerbated asthma, and in asthma associated with allergic rhinitis. A trial is recommended in such individuals prior to stepping up to step 3

- Always treat coexisting allergic rhinitis with a separate nasal steroid with or without antihistamines to prevent asthma triggering from nasal inflammation.

Long-acting Antimuscarinic Agent

- The addition of a LAMA is an option for adult patients who are on maintenance moderate-dose ICS/LABA who experience one or more asthma exacerbations in the previous year. This therapy may be of particular benefit in patients who have both asthma and COPD

- Add-on Spiriva Respimat (tiotropium) allows patients to continue with their moderate strength ICS/LABA MART regimen and is the LAMA of choice. For those on the traditional regimen (using MDI devices), the alternative is to switch to the triple therapy inhaler, low-strength Trimbow MDI (beclometasone dipropionate 87 mcg/ formoterol 5 mcg/glycopyrronium 9 mcg)

- For individuals at step 5 on high-strength ICS/LABA who need a LAMA, there are three options available: add-on Spiriva Respimat (tiptropium) or switching to Enerzair Breezhaler (DPI—indacaterol/glycopyrronium/mometasone) or high-strength Trimbow (MDI—beclometasone dipropionate 172 mcg/formoterol 5 mcg/glycopyrronium 9 mcg).

Table 2: Dosing and Administration of Add-on Therapies

| Spiriva Respimat | Trimbow MDI 87/5/9 | Trimbow MDI 172/5/9 | Enerzair Breezhaler | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICS Strength | LAMA only Separate ICS/LABA to be prescribed | Moderate-strength ICS (plus LABA/LAMA) | High-strength ICS (plus LABA/LAMA) | High-strength ICS (plus LABA/LAMA) |

| Dose | Two doses OD | Two doses BD (via spacer) | Two doses BD (via spacer) | One dose OD |

| Device | Soft mist inhaler (spacer can be used if preferred) | MDI | MDI | Breezhaler (DPI) |

| MDI=metered-dose inhaler; ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; ICS/LABA=inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting beta2 antagonist; LAMA=long-acting anti-muscarinic agent; LABA=long-acting bronchodilator; OD=once daily; BD=twice a day; DPI=dry-powder inhaler. | ||||

- Oral theophylline is a further add-on therapy that can be trialled at step 5 (usually done on the recommendation of secondary care). Always review response to add-on therapies and discontinue if ineffective.

Referral/Specialist Therapy

- Patients whose asthma remains uncontrolled despite moderate-dose ICS/LABA with or without additional controller agents have difficult-to-control or severe asthma. A proportion of these will have an alternative or coexistent condition that is contributing to their symptoms. Objective and structured evaluation can help identify and treat these conditions. Patients with suspected occupational asthma should be referred

- Some individuals will have severe eosinophilic asthma and will require high-dose ICS/LABA combination inhalers. Others may have neutrophilic asthma and may benefit from treatments such as azithromycin

- Patients receiving two or more courses of oral steroids in a 12-month period despite adherence with optimised therapy should be referred

- There are a number of biological therapies licensed for severe asthma for individuals experiencing three or more exacerbations requiring oral steroids a year. These can be prescribed where appropriate following review by a specialist in severe asthma, and discussion in a multi-disciplinary team.

Stepping Down

- All asthma guidelines recommend a step-wise approach including the need to consider stepping down therapy once control is achieved and maintained

- High-dose ICS carries a risk of systemic side effects (adrenal suppression, growth retardation, decrease in bone mineral density, and cataracts) and these risks should be balanced against the benefits

- Reductions in asthma therapy should be considered if a patient has had complete asthma control over a 3-month period

- A decision to step down should take into account how difficult it was to achieve stability and also whether previous step-down attempts have resulted in exacerbations

- Seasonal variation in symptoms should be considered

- Stop or reduce the dose of medicines in an order that takes into account the clinical effectiveness when the medicine was introduced, side effects, and the person’s preference

- It is recommended that the dose of ICS is reduced by no more than 50% each time. The risks and benefits of dose reduction should be discussed with patients and their carers.

Self-management and Asthma Action Plans

- Self-management should include a written personalised asthma action plan containing advice on how to recognise a loss of asthma control (peak flow monitoring or symptoms) and what action to take to regain control, including when to start oral steroids and seek emergency advice

- Patients should be prescribed a peak flow meter to aid self-management

- Best peak flow should be ascertained when treatment is optimised and symptoms are stable. Best peak flow is more accurate than predicted peak flow. Trigger points should be individualised, but as a guide, oral steroids are usually required when peak flow reaches 60% or less of best, and emergency review is usually necessary when peak flow reaches 50% or less of best

- There is evidence that quadrupling ICS dose when asthma control starts to deteriorate (peak flow=80% best) can reduce the risk of an exacerbation. In those individuals prescribed anti-inflammatory reliever/MART therapy, this will be achieved through increased use of PRN reliever doses of their ICS/formoterol inhaler.

For further information on asthma control and action plans, including information on how to achieve a quadrupling in ICS as part of personalised action plan in patients on a fixed-dose combination inhaler, refer to the full guideline.

Also refer to the full guideline for oral corticosteroid stewardship, exacerbations/emergency treatment (AIR/MART), a template for asthma review, additional information on the provision of national steroid treatment cards, and a table on the inhaled steroid dose equivalence of inhalers available to treat asthma.