Overview

This is a summary of NICE's guideline on assessment and diagnosis of chest pain of recent onset. It covers recommendations on provision of information for patients, managing people presenting with acute and stable chest pain, and includes assessment and referral algorithms. This summary has been created for use by primary care health professionals. For the complete set of recommendations, refer to the full guideline.

Providing Information for People with Chest Pain

- Discuss any concerns people (and where appropriate their family or carer/advocate) may have, including anxiety when the cause of the chest pain is unknown. Correct any misinformation

- Offer people a clear explanation of the possible causes of their symptoms and the uncertainties

- Clearly explain the options to people at every stage of investigation. Make joint decisions with them and take account of their preferences:

- encourage people to ask questions

- provide repeated opportunities for discussion

- explain test results and the need for any further investigations

- Provide information about any proposed investigations using everyday, jargonfree language. Include:

- their purpose, benefits and any limitations of their diagnostic accuracy

- duration

- level of discomfort and invasiveness

- risk of adverse events

- Offer information about the risks of diagnostic testing, including any radiation exposure

- Address any physical or learning difficulties, sight or hearing problems and difficulties with speaking or reading English, which may affect people’s understanding of the information offered

- Offer information after diagnosis as recommended in the relevant disease management guidelines[A]

- Explain if the chest pain is non-cardiac and refer people for further investigation if appropriate

- Provide individual advice to people about seeking medical help if they have further chest pain

People Presenting with Acute Chest Pain

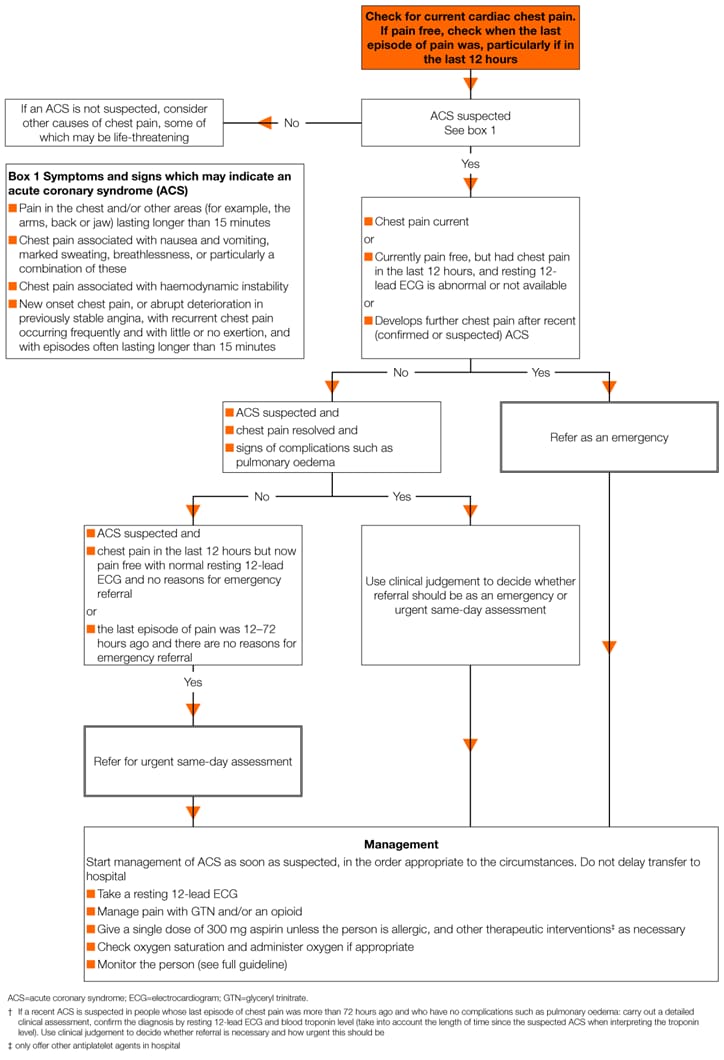

Algorithm 1: Acute Chest Pain Pathway—Initial Assessment and Referral to Hospital for Recent† Acute Chest Pain of Suspected Cardiac Origin

The algorithm should be read with the recommendations in this document.

This section of the guideline covers the assessment and diagnosis of people with recent acute chest pain or discomfort, suspected to be caused by an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The term ACS covers a range of conditions including unstable angina, ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

Initial Assessment and Referral to Hospital

- Check immediately whether people currently have chest pain. If they are pain free, check when their last episode of pain was, particularly if they have had pain in the last 12 hours

- Determine whether the chest pain may be cardiac and therefore whether this guideline is relevant, by considering:

- the history of the chest pain

- the presence of cardiovascular risk factors

- history of ischaemic heart disease and any previous treatment

- previous investigations for chest pain

- Initially assess people for any of the following symptoms, which may indicate an ACS:

- pain in the chest and/or other areas (for example, the arms, back or jaw) lasting longer than 15 minutes

- chest pain associated with nausea and vomiting, marked sweating, breathlessness, or particularly a combination of these

- chest pain associated with haemodynamic instability

- new onset chest pain, or abrupt deterioration in previously stable angina, with recurrent chest pain occurring frequently and with little or no exertion, and with episodes often lasting longer than 15 minutes

- Do not use people’s response to glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) to make a diagnosis

- Do not assess symptoms of an ACS differently in men and women. Not all people with an ACS present with central chest pain as the predominant feature

- Do not assess symptoms of an ACS differently in ethnic groups. There are no major differences in symptoms of an ACS among different ethnic groups

- Refer people to hospital as an emergency if an ACS is suspected and:

- they currently have chest pain or

- they are currently pain free, but had chest pain in the last 12 hours, and a resting 12-lead ECG is abnormal or not available

- If an ACS is suspected and there are no reasons for emergency referral, refer people for urgent same-day assessment if:

- they had chest pain in the last 12 hours, but are now pain free with a normal resting 12-lead ECG or

- the last episode of pain was 12–72 hours ago

- Refer people for assessment in hospital if an ACS is suspected and:

- the pain has resolved and

- there are signs of complications such as pulmonary oedema

- Use clinical judgement to decide whether referral should be as an emergency or urgent same-day assessment

- If a recent ACS is suspected in people whose last episode of chest pain was more than 72 hours ago and who have no complications such as pulmonary oedema:

- carry out a detailed clinical assessment

- confirm the diagnosis by resting 12-lead ECG and blood troponin level

- take into account the length of time since the suspected ACS when interpreting the troponin level

- Use clinical judgement to decide whether referral is necessary and how urgent this should be

- Refer people to hospital as an emergency if they have a recent (confirmed or suspected) ACS and develop further chest pain

- When an ACS is suspected, start management immediately in the order appropriate to the circumstances and take a resting 12-lead ECG. Take the ECG as soon as possible, but do not delay transfer to hospital

- If an ACS is not suspected, consider other causes of the chest pain, some of which may be life-threatening

Resting 12-lead ECG

- Take a resting 12-lead ECG as soon as possible. When people are referred, send the results to hospital before they arrive if possible. Recording and sending the ECG should not delay transfer to hospital

- Follow local protocols for people with a resting 12-lead ECG showing regional ST-segment elevation or presumed new left bundle branch block (LBBB) consistent with an acute STEMI until a firm diagnosis is made. Continue to monitor

- Follow the NICE guideline on unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management (CG94) for people with a resting 12-lead ECG showing regional ST-segment depression or deep T wave inversion suggestive of a NSTEMI or unstable angina until a firm diagnosis is made. Continue to monitor

- Even in the absence of ST-segment changes, have an increased suspicion of an ACS if there are other changes in the resting 12-lead ECG, specifically Q waves and T wave changes. Consider following the NICE guideline on unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management (CG94) if these conditions are likely. Continue to monitor

- Do not exclude an ACS when people have a normal resting 12-lead ECG

- If a diagnosis of ACS is in doubt, consider:

- taking serial resting 12-lead ECGs

- reviewing previous resting 12-lead ECGs

- recording additional ECG leads

- Use clinical judgement to decide how often this should be done. Note that the results may not be conclusive

- Obtain a review of resting 12-lead ECGs by a healthcare professional qualified to interpret them as well as taking into account automated interpretation

- If clinical assessment and a resting 12-lead ECG make a diagnosis of ACS less likely, consider other acute conditions. First consider those that are life-threatening such as pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection or pneumonia. Continue to monitor

Immediate Management of a Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome

- Management of ACS should start as soon as it is suspected, but should not delay transfer to hospital. The recommendations in this section should be carried out in the order appropriate to the circumstances

- Offer pain relief as soon as possible. This may be achieved with GTN (sublingual or buccal), but offer intravenous opioids such as morphine, particularly if an acute myocardial infarction (MI) is suspected

- Offer people a single loading dose of 300 mg aspirin as soon as possible unless there is clear evidence that they are allergic to it

- If aspirin is given before arrival at hospital, send a written record that it has been given with the person

- Only offer other antiplatelet agents in hospital. Follow appropriate guidance (the NICE guideline on unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management or local protocols for STEMI)

- Do not routinely administer oxygen, but monitor oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry as soon as possible, ideally before hospital admission. Only offer supplemental oxygen to:

- people with oxygen saturation (SpO2) of less than 94% who are not at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure, aiming for SpO2 of 94–98%

- people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure, to achieve a target SpO2 of 88–92% until blood gas analysis is available

- Monitor people with acute chest pain, using clinical judgement to decide how often this should be done, until a firm diagnosis is made. This should include:

- exacerbations of pain and/or other symptoms

- pulse and blood pressure

- heart rhythm

- oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry

- repeated resting 12-lead ECGs and

- checking pain relief is effective

- Manage other therapeutic interventions using appropriate guidance (the NICE guideline on unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management or local protocols for STEMI)

Making a Diagnosis

- When diagnosing MI, use the universal definition of myocardial infarction. This is the detection of rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarkers values [preferably cardiac troponin (cTn)] with at least one value above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit and at least one of the following:

- symptoms of ischaemia

- new or presumed new significant ST-segment-T wave (ST-T) changes or new left bundle branch block (LBBB)

- development of pathological Q waves in the ECG

- imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality

- identification of an intracoronary thrombus by angiography

- When a raised troponin level is detected in people with a suspected ACS, reassess to exclude other causes for raised troponin (for example, myocarditis, aortic dissection or pulmonary embolism) before confirming the diagnosis of ACS

- When a raised troponin level is detected in people with a suspected ACS, follow the appropriate guidance (the NICE guideline on unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management or local protocols for STEMI) until a firm diagnosis is made. Continue to monitor

- When a diagnosis of ACS is confirmed, follow the appropriate guidance (the NICE guideline on unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management or local protocols for STEMI)

- Reassess people with chest pain without raised troponin levels and no acute resting 12-lead ECG changes to determine whether their chest pain is likely to be cardiac

- If myocardial ischaemia is suspected, follow the recommendations on stable chest pain in this guideline. Use clinical judgement to decide on the timing of any further diagnostic investigations

- Do not routinely offer non-invasive imaging or exercise ECG in the initial assessment of acute cardiac chest pain

- Only consider early chest computed tomography (CT) to rule out other diagnoses such as pulmonary embolism or aortic dissection, not to diagnose ACS

- Consider a chest X-ray to help exclude complications of ACS such as pulmonary oedema, or other diagnoses such as pneumothorax or pneumonia

- If an ACS has been excluded at any point in the care pathway, but people have risk factors for cardiovascular disease, follow the appropriate guidance, for example, the NICE guidelines on cardiovascular disease and hypertension in adults

People Presenting with Stable Chest Pain

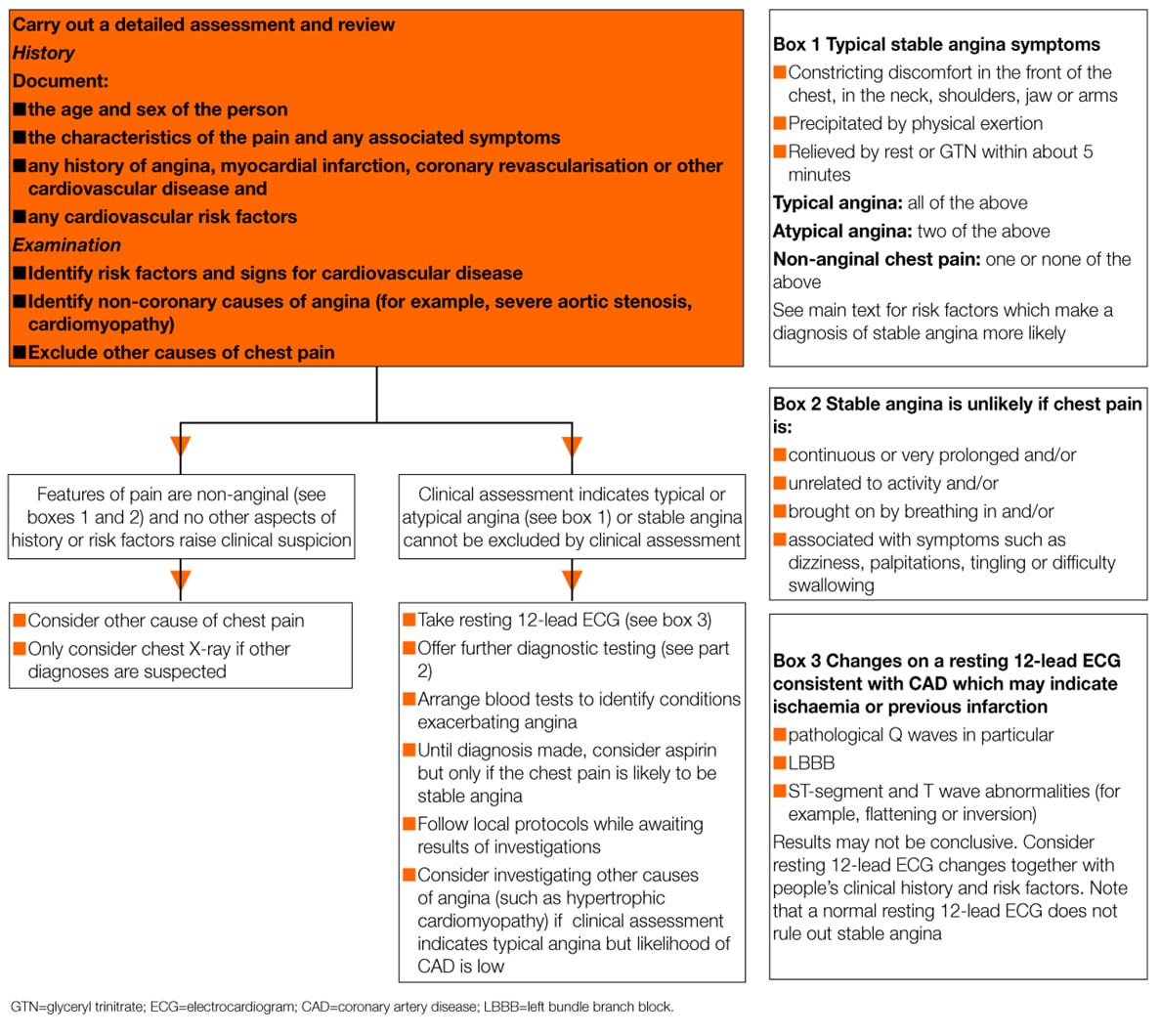

Algorithm 2: Stable Chest Pain Pathway—Presentation

The algorithm should be read with the recommendations in this document.

This section of the guideline addresses the assessment and diagnosis of intermittent stable chest pain in people with suspected stable angina.

- Exclude a diagnosis of stable angina if clinical assessment indicates non-anginal chest pain and there are no other aspects of the history or risk factors raising clinical suspicion

- If clinical assessment indicates typical or atypical angina, offer diagnostic testing

Clinical Assessment

- Take a detailed clinical history documenting:

- the age and sex of the person

- the characteristics of the pain, including its location, radiation, severity, duration and frequency, and factors that provoke and relieve the pain

- any associated symptoms, such as breathlessness

- any history of angina, MI, coronary revascularisation or other cardiovascular disease and

- any cardiovascular risk factors

- Carry out a physical examination to:

- identify risk factors for cardiovascular disease

- identify signs of other cardiovascular disease

- identify non-coronary causes of angina (for example, severe aortic stenosis, cardiomyopathy) and

- exclude other causes of chest pain

Making a Diagnosis Based on Clinical Assessment

- Assess the typicality of chest pain as follows:

- presence of three of the features below is defined as typical angina

- presence of two of the three features below is defined as atypical angina

- presence of one or none of the features below is defined as non-anginal chest pain

- Anginal pain is:

- constricting discomfort in the front of the chest, or in the neck, shoulders, jaw or arms

- precipitated by physical exertion

- relieved by rest or GTN within about 5 minutes

- Do not define typical and atypical features of anginal chest pain and non-anginal chest pain differently in men and women

- Do not define typical and atypical features of anginal chest pain and non-anginal chest pain differently in ethnic groups

- Take the following factors, which make a diagnosis of stable angina more likely, into account when estimating people’s likelihood of angina:

- age

- whether the person is male

- cardiovascular risk factors including:

- a history of smoking

- diabetes

- hypertension

- dyslipidaemia

- family history of premature coronary artery disease (CAD)

- other cardiovascular disease

- history of established CAD, for example, previous MI, coronary revascularisation

- Unless clinical suspicion is raised based on other aspects of the history and risk factors, exclude a diagnosis of stable angina if the pain is non-anginal (see above). Features which make a diagnosis of stable angina unlikely are when the chest pain is:

- continuous or very prolonged and/or

- unrelated to activity and/or

- brought on by breathing in and/or

- associated with symptoms such as dizziness, palpitations, tingling or difficulty swallowing

- Consider causes of chest pain other than angina (such as gastrointestinal or musculoskeletal pain)

- Consider investigating other causes of angina, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, in people with typical angina-like chest pain and a low likelihood of CAD

- Arrange blood tests to identify conditions which exacerbate angina, such as anaemia, for all people being investigated for stable angina

- Only consider chest X-ray if other diagnoses, such as a lung tumour, are suspected

- If a diagnosis of stable angina has been excluded at any point in the care pathway, but people have risk factors for cardiovascular disease, follow the appropriate guidance, for example, the NICE guideline on cardiovascular disease and the NICE guideline on hypertension in adults

- For people in whom stable angina cannot be excluded on the basis of the clinical assessment alone, take a resting 12-lead ECG as soon as possible after presentation

- Do not rule out a diagnosis of stable angina on the basis of a normal resting 12-lead ECG

- Do not offer diagnostic testing to people with non-anginal chest pain on clinical assessment unless there are resting ECG ST-T changes or Q waves

- A number of changes on a resting 12-lead ECG are consistent with CAD and may indicate ischaemia or previous infarction. These include:

- pathological Q waves in particular

- LBBB

- ST-segment and Twave abnormalities (for example, flattening or inversion)

- Note that the results may not be conclusive

- Consider any resting 12-lead ECG changes together with people’s clinical history and risk factors

- For people with confirmed CAD (for example, previous MI, revascularisation, previous angiography) in whom stable angina cannot be excluded based on clinical assessment alone, see recommendation 1.3.4.4 of the full guideline about functional testing

- Consider aspirin only if the person’s chest pain is likely to be stable angina, until a diagnosis is made. Do not offer additional aspirin if there is clear evidence that people are already taking aspirin regularly or are allergic to it

- Follow local protocols for stable angina while waiting for the results of investigations if symptoms are typical of stable angina

Footnote

[A] For example, the NICE guidelines on unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management (CG94), stable angina: management (CG126), generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults (CG113) and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults (CG184)